The Power of Networks (Part 8)

By Asher Crispe: February 20, 2013: Category Inspirations, Networks of Meaning

Today when we speak of social hangouts or places to ‘get together,’ these meeting spaces enable us to hopefully become closer to one another and develop our relationships. In the Torah, we find the example of the altar (mizbeach) as a unique object in the portable sanctuary or Tabernacle (Mishkan) which symbolizes our capacity for closeness and for repairing and maintaining relations. The altar serves as a designated location for offering sacrifices or “korbanot” which stems from the word “karav” meaning to “come near” or “approach.” In a nutshell, transgressive acts wear and tear at the fabric of our relationships and in doing so create distance. Once we feel disconnected or estranged in a relationship we need to do some mending in order to reestablish the lost closeness and the intimate intensity of the connection. We accomplish this via the sacrifice of ‘animals,’ which in a kabbalistic universe denotes a killing of the coarseness of the ego (the animality of the soul) and offering its vitality (the life-force that energized the original transgressive act) towards positive ends whereby it is consumed in fire (deconstructed from its original form) and sublimated.

Today when we speak of social hangouts or places to ‘get together,’ these meeting spaces enable us to hopefully become closer to one another and develop our relationships. In the Torah, we find the example of the altar (mizbeach) as a unique object in the portable sanctuary or Tabernacle (Mishkan) which symbolizes our capacity for closeness and for repairing and maintaining relations. The altar serves as a designated location for offering sacrifices or “korbanot” which stems from the word “karav” meaning to “come near” or “approach.” In a nutshell, transgressive acts wear and tear at the fabric of our relationships and in doing so create distance. Once we feel disconnected or estranged in a relationship we need to do some mending in order to reestablish the lost closeness and the intimate intensity of the connection. We accomplish this via the sacrifice of ‘animals,’ which in a kabbalistic universe denotes a killing of the coarseness of the ego (the animality of the soul) and offering its vitality (the life-force that energized the original transgressive act) towards positive ends whereby it is consumed in fire (deconstructed from its original form) and sublimated.

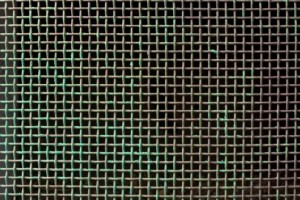

These relationships are not limited to the human sphere but also include our relationship with the Divine. On some level, these two types of relation are intertwined and interdependent. All of the design features of the altar hold mystical significance for the production of improvements and transformations within the intersubjective realm as well as human-Divine encounters. Each detail signifies another ingredient that is integral to this process. Once such feature is mentioned in Shemot/Exodus (27:4) “Make for it [the altar] a net (mikbar) of copper meshwork (reshet) and upon the network (reshet) you will make four copper rings at its four edges.” Two words stand out in this verse that are particular to our discussion of networks. The first one is reshet (network or netting) which appears twice while the second is mikbar which means something akin to a ‘net,’ ‘grate’ or ‘sieve.’ In the next verse (Shemot/Exodus 27:5), we learn about its position: “You shall place it under the surrounding border of the altar from below, and the meshwork (reshet) shall go to the midpoint of the altar.”

From this we see that a network is needed which surrounds or encompasses the altar (which is itself the space for working on social-spiritual closeness). This informs us that we are all connected. Moreover, it is a source for a ‘social network’ in the Torah–an all inclusive network which defines our ability to come close. Next we find that it is extended downward and reaches the middle (there is some difference of opinion as to if it belongs to the top half, middle or bottom half of the height of the altar which we cannot go into right now). Let us simply say that it has a mediating quality between the top and bottom halves of the altar (which themselves would receive the ‘blood’ of different sacrifices depending on the type of repair being made).

The key interpretation for this in the Talmud (Zevachim 53a) maintains that the Torah is introducing a divider “to distinguish between the higher bloods and the lower bloods.” Higher and lower bloods may represent two types of vitality that have to be offered. Why have a network in the form of a copper sieve to reinforce this distinction? Looking closely at the word damim or “bloods” [דמים] we might suggest that the expression strongly resembles another fundamental distinction in the Torah which is between the higher and lower waters where mayim (waters [מים]) is literally inside the word for “bloods.” This idea is further strengthened by the transformation of water into blood in the first of the Ten Plagues in Egypt. The higher and lower waters are a reference to the twofold source of the flood in the times of Noach/Noah as we mentioned previously. Once again, the lower waters relate to the outpouring of the natural sciences (chochmat ha’teva) which includes all of science and technology, while the higher waters are a manifestation of the inner dimensions of the Torah. Another way of putting it might be to understand the water sources as Divine (transcendent and revealed from on High) and immanent (given over to human intellect which uncovers them within Creation).

Given all of this, we can now comprehend why this divider is a kind of filter (sieve) and extends from the top down. If the vitality (higher bloods) is for the Torah in the formal sense, then it is meant to descend down into our vitality (lower bloods) which is for science (natural wisdom). For a proper interaction we require a filtering mechanism or membrane which both distinguishes them and allows them to come together (the network both separates and unites in that everyone is assigned their own domain (reshut from reshit “network”) which distances us one from the next and yet links up between those domains effectively collapsing that distance). If the network affect were extended from the bottom up, this would be like saying that science should determine Torah (which would be highly problematic in that the Torah is whole and complete while science is always partial and incomplete). Therefore, we are instructed to work top-down in order to emphasize how the Torah is supposed to influence and inspire science but from a privileged position within the relationship. Thus, Torah comes down to science while science has to work its way up to the Torah. The interactions are then networked via the filtering system which is positioned in the middle as a kind of mediator.

From this we can surmise that the altar brings closeness to distanced and estranged ideas as well as people. There is a whole society of ideas which suffers from the same damaged relations to the point where one idea cannot relate to another idea. The fire on the altar may also serve to deconstruct the coarseness of unrefined ideas and create new synergies as a result. On an even deeper level, the Torah in the broadest sense can be found to encompass a more restricted sense of Torah with that of science (the idea of a meta-Torah which bridges both) and the allusion to this as a final objective of the copper meshwork interface is found in the words of the verse itself (Shemot/Exodus 27:4) in that “make for it [the altar] a net (mikbar)of copper meshwork (reshet)” which in Hebrew is “v’asita lo mikbar ma’esh reshet nachoshet” with the last letters of the first four words being Tav, Vav, Reish, Hei which spells out the word Torah (Sefer Ha’Remezim L’Rabbeinu Yoel p.316). In sum, the whole purpose of the Torah is to make peace (just as that altar embodies that same objective). Since the ‘final letters’ of the description of network on the altar are intended to hint at the Torah and its goal of bring unity into all of reality, we may subsequently look to the Torah for the ability to link everything (distant and close, high and low) together.

From this we can surmise that the altar brings closeness to distanced and estranged ideas as well as people. There is a whole society of ideas which suffers from the same damaged relations to the point where one idea cannot relate to another idea. The fire on the altar may also serve to deconstruct the coarseness of unrefined ideas and create new synergies as a result. On an even deeper level, the Torah in the broadest sense can be found to encompass a more restricted sense of Torah with that of science (the idea of a meta-Torah which bridges both) and the allusion to this as a final objective of the copper meshwork interface is found in the words of the verse itself (Shemot/Exodus 27:4) in that “make for it [the altar] a net (mikbar)of copper meshwork (reshet)” which in Hebrew is “v’asita lo mikbar ma’esh reshet nachoshet” with the last letters of the first four words being Tav, Vav, Reish, Hei which spells out the word Torah (Sefer Ha’Remezim L’Rabbeinu Yoel p.316). In sum, the whole purpose of the Torah is to make peace (just as that altar embodies that same objective). Since the ‘final letters’ of the description of network on the altar are intended to hint at the Torah and its goal of bring unity into all of reality, we may subsequently look to the Torah for the ability to link everything (distant and close, high and low) together.

In Part Nine, we will move on to explain the meaning of the four rings which were mounted on top of the network of the altar in order to transport it.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-power-of-networks-part-9/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-power-of-networks-part-7/

The Power of Networks (Part 8),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)