The Pathos of Breaking Bad (Part 2)

By Asher Crispe: February 17, 2014: Category Inspirations, Quilt of Translations

When you’re already heading downhill it is easy to pick up speed, slide and even tumble out of control. Our momentum carries us. Braking is another story completely. The energy required to stop, to go against the natural inclination that has been coordinated with the force of gravity, is huge. Even more taxing is the strength required for reversing course and heading back up the hill.

When you’re already heading downhill it is easy to pick up speed, slide and even tumble out of control. Our momentum carries us. Braking is another story completely. The energy required to stop, to go against the natural inclination that has been coordinated with the force of gravity, is huge. Even more taxing is the strength required for reversing course and heading back up the hill.

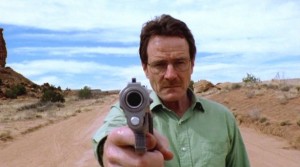

Walter White is a man heading down hill–fast. If we drop a pin on this map and locate ourselves at our personal peak–the position of uncompromised integrity, then every step that takes us down from that height reduces our view of our surroundings and makes concessions to substandard living conditions. For Walt, this happens when he first considers going outside the law to make some money to pay for his cancer treatment and provide for his family. Noble ends tethered to dubious means portends a losing situation.

In the spirit of know-all intellectualism, Walt thinks on his feet and formulates a plan. Only nothing ever goes according to plan. The life of the mind can never fully simulate real life. There is no algorithmic chemistry that yields entirely predictable results every time you try it. One of the charming qualities of Breaking Bad is how it manages to humanize the most grotesque criminal situations. In all our comedy of errors, audiences cannot help but sympathize with Walt as he digs himself into a deeper and deeper hole. At first he seems so committed to only stepping over the line of moral and legal acceptability with one foot. Straddling it in this fashion, it remains in full view as expressed by his lingering discomfort. He knows he is overextended but tells himself that it is OK because extraordinary circumstances warrant it. He only breaks bad a ‘tiny’ bit. What’s a little Meth? Didn’t we at one time legally sell this stuff? Isn’t the law here somewhat arbitrary? No harm, no foul when it comes to consenting adults. Besides, he needs the money.

Episode after episode we follow the same internal game. Walt keeps facing unintended consequences–the sort of blind alleys and hidden cull-de-sacs that emerge from the twists and turns of events that break from the designated plan. He cooks the drugs once and find that it’s not enough so he reasons that ‘not enough is not enough’ and cooks some more. He is even taken by surprise at the thrill of living on the edge (at least at the beginning while something resembling an edge is still visible). But what about when he has to up the ante? Will he kill or be killed?

Originally he never thought he would have to kill someone. He just wanted to make money selling illegal drugs but he naively felt that this kind of transaction would go down the same way one sells DVDs or baseball cards on eBay. That another established drug dealer would find his little operation an encroachment on his territory and the impetus for a turf war, was unimaginable. Yet, it happens. Once again, Walt must weight the morality of killing a human being (who is tied up and defenseless the first time it happens) verses his fear that if let go (after all he cannot bring him to the police on account of his first transgression i.e. selling drugs himself) this guy will find and kill all of Walt’s family in retribution. Somehow, the very thing he wanted to preserve–his family–was now potentially endangered by way of the very actions he took to ensure their well being. Turning up the ‘moral ambiguity’ argument in his head, Walt succeeds in rationalizing why murder is acceptable (but regrettable) because circumstances call for it. After all, he too is a victim of these circumstances. The wide angle shot of these events we contemplate in our minds presents the relative ease with which one step over the line becomes two and then three with each one carrying a person further away from a ‘kosher’ lifestyle. Descent gets easier and easier.

If we had to pick one sterling example from out of the rabbinic tradition that sums up the entirely of Breaking Bad, then we have to cite the Ethics of the Fathers (Pirkei Avot) 4:2 where Ben Azzai says:

“Run to perform even an easy mitzvah [good deed], and flee from transgression; for one good deed brings about another, and one transgression brings about another; for the rewards for a good deed is a good deed, and recompense of a transgression is a transgression.”

To put it differently, one could suggest that Breaking Bad is nothing more than a 62 episode commentary on this Ben Azzai teaching. It is a powerful way to hyperbolically envision what each of us may come to struggle with in our daily decisions. Sometimes the best way to learn to recognize something subtle which is happening within our psyche is to magnify it 1000 times over until it can be projected in truly absurd proportions right in front of us. Once observed in a blown up manner, a person who embraces self-reflection as a way to personal improvement, can ideally locate those same traits within the self on a variety of scales. ‘There it is lurking within me’ but I never identified it until it was placed before me as an object for study in high resolution.

Taking about Ben Azzai’s statement, we can distinguish several components which are rolled into it. First, the easy, good deed–in Hebrew refers to a ‘light’ (in the sense of ‘insignificant’) good deed. Not that any good deed is ever insignificant but, as the commentators point out, it is lightly esteemed in the eyes of the beholder. This refers to all sorts of things that are too easily taken for granted. They seem like no big deal. And because we subjectively relate to them as such, we might be prone to passing them by or ignoring them when they are inconvenient. ‘Let me worry about the big stuff.’ However, Ben Azzai is emphasizing that if you trample things after falsely labeling them of minimal importance (moral lines for instance) then pretty soon you will find yourself sailing past the heavy stuff. This was how selling narcotics snowballed into multiple counts of murder, blackmail, kidnapping and innumerable other transgressions for Walter White. Apparently the common advice that instructs us to ‘not sweat the small stuff’ has its limits.

A cautionary tale–don’t assume you know how to weight anything when it comes to its ultimate moral significance. The act of measurement limits our perception and may be wielded for exploitive purposes. Advice to the potential Walter White within ourselves–consider it all to be heavy. Everything is significant. Details matter. Fine lines matter. Once things start to blur, the downward spiral commences. Thus, dialectically, Ben Azzai adds to flee from transgression. This is a high-stakes game and it warrants running to the positive and away from the negative. Run, don’t walk. If we tarry too long we might have time to craft a counter argument in favor of breaking bad. The ‘Id’ or Yeitzer Hara will give a shot at knocking down any moral or spiritual line if afforded enough time to sound convincing.

Next, Ben Azzai evokes a hallmark of behavioral theory: it gets easier with time. The more one practices the unfamiliar, the more it becomes an automatic response which can be accomplished without thinking (or feeling as the case may be). The first time Walt kills he is devastated by it. When the moral compass remains somewhat intact (before all of the magnetic interference that was caused by his attraction to money and power) there remains some semblance of a guilty conscience. The truth hurts and cannot be ignored. What is so artfully demonstrated by the writers and actors on the show is the degradation of ethical sobriety. Positive and Negative behaviors are self-reinforcing.

Each repetition puts us deeper into the groove. We become acclimatized to our actions. They have a pull. Hence, a good deed naturally leads to another good deed while a negative actions gets entangled with other negative actions. In both cases, we are speaking of networks. Even the word for a good deed (mitzvah) contains the dual notions of a ‘commandment’ as well as being a ‘connection’ (tzav’ta u’chibur).

Consequently every imperative connection leads to greater connectivity. An interactive network such as the human brain has shown that our behaviors actually build synaptic connections. Likewise, trip on a power line and the probability of overloading other wires on the grid increases. The transgression is tantamount to the severing of a connection or the loss of relationship and reliability. As we follow Walt through his journey of moral decay, we can attest to the loss of connection that occurs between him and his friends and family. He also becomes demonstrably out of touch with himself. Here is a man in need of a reality check.

Consequently every imperative connection leads to greater connectivity. An interactive network such as the human brain has shown that our behaviors actually build synaptic connections. Likewise, trip on a power line and the probability of overloading other wires on the grid increases. The transgression is tantamount to the severing of a connection or the loss of relationship and reliability. As we follow Walt through his journey of moral decay, we can attest to the loss of connection that occurs between him and his friends and family. He also becomes demonstrably out of touch with himself. Here is a man in need of a reality check.

Finally Ben Assai, addresses the ‘reward’ aspect that is associated with a type of behavior. Not only does the behavior grease the skids to keep up the momentum of our chosen direction in life, the consequences thereof are embedded in the behavior itself. The Torah notion of ‘reward’ and ‘punishment’ is akin to what we call ‘feedback’ in a cybernetic system. Both positive and negative feedback are ‘rewarding’ in that they carry a benefit to recipient (the Hebrew text even used the word s’kar or ‘reward’ in both cases but without intending to sound sarcastic when claiming a ‘reward for a transgression is a transgression’). Walt does not have to be hit by lightning. His paranoia and lack of connection with those he cares about and the total loss of his former family life over the course of the show, prove that the transgressions carry within them their own negative feedback. Likewise, when we strive to connect, the feeling of connection is itself rewarding.

In Part Three we will explore just how low a person can go.

The Pathos of Breaking Bad (Part 2),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

Dear Rabbi Crispe,

We, my Rebbetzin and “I” are coming to close of Breaking Bad. Your

analysis has helped us to understand/rationalize the time spent on the first 58 episodes. Wishing and yours a zissen Pesach.

The ‘Bear’ Family