The “Organization” of Law (Part 3)

By Asher Crispe: April 3, 2014: Category Inspirations, Quilt of Translations

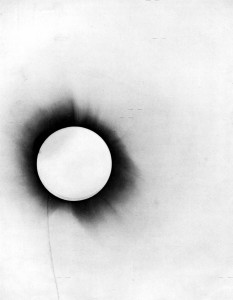

Have you ever thought about things that were missing? Does not the absence of something–its negation from the scene–in an elliptical way call attention to it? When we experience a ‘run’ in the soul (the leaving of containment and limitation) an impression or trace is left upon the vacated space that was left behind. This is the force of the ‘feminine’ in Kabbalah as it pertains to prohibitions in law. ‘Our’ definition (self-definition) can paradoxically stem both from the removal of something and from the assertion of something. In deciding to purposely avoid concrete expression, the prohibited announces itself to the intellect as an abstraction much like a photographic negative (which is nevertheless integral to deciphering the overall image).

Have you ever thought about things that were missing? Does not the absence of something–its negation from the scene–in an elliptical way call attention to it? When we experience a ‘run’ in the soul (the leaving of containment and limitation) an impression or trace is left upon the vacated space that was left behind. This is the force of the ‘feminine’ in Kabbalah as it pertains to prohibitions in law. ‘Our’ definition (self-definition) can paradoxically stem both from the removal of something and from the assertion of something. In deciding to purposely avoid concrete expression, the prohibited announces itself to the intellect as an abstraction much like a photographic negative (which is nevertheless integral to deciphering the overall image).

For this reason, the negative commandments (prohibitions)—rather than being a felt presence or direct action—are assigned to the domain of insights and understandings which perceive the inadequacy or problematic implications of a given action and choose to not pursue it. This nonetheless translates into positive knowledge in that I now know what not to do. Putting a spin on the motto of ‘success through failure,’ we may not have the words with which to formulate how things should be but we have made progress in that direction as we can attest to what constitutes the wrong way. Whatever the final picture, it cannot include these things. They have be prescreened. We acknowledge the danger or undesirability by canceling the performance and in doing so keep our distance. Would this not explain why it is so much easier to conceive of dystopic futures than detail a wished-for utopia?

Often too overconfident that our activities must be spelled out, our submission to explicit forms of representation–the said and stated–stumbles upon the limits of this approach. In a post-modern era, our suspicion of representation, clarity, presence and manifestation has given way to a rehabilitation of non-representational thinking and the ‘play of the negative.’ Accepting that reality is saturated with experiences which overflow the conventions of language, we venture in the the realm of the unsayable, the inexpressible, welcoming the mystery, the ambiguity, and the unknowability which awaits us.

In this view, the unsaid and the unsayable are repositioned above the said. Caught in a knot of ‘nots’ we resign ourselves to epistemological limits which also participate in the forging of our identity indirectly. Concretely I might say ‘I don’t do drugs’ or alternatively declare myself to be ‘straight edge’ (an adherent to a social movement which refrains from drug use). Similarly, you are a good person because you don’t lie, cheat and steal.

Continuing with morphological correspondences, our sense of recoil makes the feminine mode of being into a ‘runaway bride’ of sorts. In Hebrew, the kallah or bride alludes to the idea of kallut ha’nefesh which, while often translated as the ‘expiration of the soul,’ more technically denotes the exodus of spirit from a containment vessel. It is the run which rejects a particular form of embodiment. For instance, if I am uncomfortable with a linguistic assertion about myself (a predicative ‘cap’ perhaps), I may seek refuge in a mysterious cloud that is without limit. Fueled by the feeling that I am always more than what is said about me, my identity becomes veiled from those who attempt to gaze at me through the lens of language.

Just as the reading of the word for bride (kallah) entails a desire for upward transcendence, the decoding of the word for groom (chatan) derives from the downward move towards immanence (according to the Talmud Yevamot 63a ‘to descend a level –nechat darga]’). On the surface of this passage it would appear that we are speaking about the marriage of men and women only. In classic ‘old school’ fashion the advice to many a man is to marry beneath him because a woman who is of higher status might not accept the accommodations and lifestyle he provides for her.

However, the inner dimension of the Talmud is giving a description of dynamics within the soul of every one of us. Marrying the negative, the unsaid to the said, trying to contain the uncontainable, is a tricky business. If a positive ‘masculine’ assertion attempts to marry a ‘feminine’ unrepresentable quality which is too high (i.e. it greatly exceeds the capacity for words) then the marriage might not endure or it will consist of continual conflict–a struggle between trying to sew up definitions of a person or experience and the bursting forth that tears the stitches, bleeding out into the undefined or undefinable. The positive affirmation seeks to tie down (agent of the marriage) that which unravels all ties. This pairing could comically (à la Steven Wright) be depicted as ‘putting a humidifier and a dehumidifier in the same room and letting them fight it out.’ He is condensation. She is evaporation. Together they must coexist.

Sustaining such a fusion is fraught with difficulty. But this is precisely what is at stake with the intrinsic fussiness of language that matures to a full bloom in the debates over clarity verses ambiguity in law. Hence, as expositors of law we are cautioned from attempting to marry too high (too transcendent) a feminine level on account of our inability to properly contain the ‘uncontainable’ of such magnitude. The ‘wealthy’ woman in this analogy is the superabundance of experiential content, the surplus sensation, the excess of meaning, which cannot live peacefully in so small and meager a home as the presented system of thought. Big, beautiful, hand-crafted concepts might stand a chance at marrying her but the generic standard issue ones which are associated with the textbook and manual will not suffice.

As a result, the masculine mode of positive expression must effect a twofold descent. One, a bringing down of the ineffable–somewhat like anchoring a balloon to keep it from floating away–and two, a compromise wherein we pursue only those candidates for marriage that might be ‘manageable’ in the first place i.e. those of a lesser level of undefinability or negativity. Ideally a balance has to be struck which maintains a semblance of containment while not asserting complete control. No totalizing definitions allowed. Openness prevails.

Drawing the abstract down has the connotation of instantiation. We acquire an emotive sense of what was before, allusive to all but the faculties of the mind. We are presented with something concrete and actionable. To now orient ourselves within kabbalistic thought, we can place each of these terms (negative/feminine and positive/masculine) within the ontological scaffolding of the essential Divine name, Yud-Hei-Vav-Hei.

Given that these four letters permute to form the word Havayah which means ‘Being,’ the correspondence of the negative commandments relates to the first two letters Yud and Hei. Modeling the unfolding of consciousness in the soul, this initial dyad represents our intuition and understanding–the powers of abstraction seated in the mind. Practically, if we always had to go out and commit a crime to learn about what not to do, we would be in deep trouble. However, due to our cognitive prowess, we can leap beyond ourselves and ‘virtually’ experience doing something without actually doing it simply by entertaining what it might be like in the theater of our imagination.

On the flip side, the letters Vav and Hei are commonly identified with the emotive spheres and our domain of influence or ‘kingdom’ which comes under the sway of our actions and attempts at self-expression. The ‘lower’ two letters are the signs for embodiment and concretized experience whereby my inner life is turning into an object. These levels parallel the positive commandments. We both feel and act upon what we posit. They are world-building expressions. By contrast, the ‘higher’ levels of the Yud– and Hei float above the world and cannot fully enter into it.

What can we take from all this? The essential Divine name signifies two counter movements within law–the positive and the negative, the do and don’t do. Their aggregation completes this proper identity (name) and pronouncement of Being (Havayah). Another interesting set of correspondences characterizes the Yud and Hei of the intellect as the ‘parents’ which belong to a previous generation or slightly different order of Being, while the Vav and Hei relate to the children–the emotional and actionable offspring of cognitive processes. Typically the ‘children’ want to do things and positively assert themselves (masculine mode of hyperactivity) while the parents continually come across as ‘out of it,’ hanging back (the feminine mode of ‘let me think about it’ when asked if one may do something). Relatively quiet and reserved, the mental parents caution us in our activities and temper the emotions whilst heaping prohibitions upon the children.

What can we take from all this? The essential Divine name signifies two counter movements within law–the positive and the negative, the do and don’t do. Their aggregation completes this proper identity (name) and pronouncement of Being (Havayah). Another interesting set of correspondences characterizes the Yud and Hei of the intellect as the ‘parents’ which belong to a previous generation or slightly different order of Being, while the Vav and Hei relate to the children–the emotional and actionable offspring of cognitive processes. Typically the ‘children’ want to do things and positively assert themselves (masculine mode of hyperactivity) while the parents continually come across as ‘out of it,’ hanging back (the feminine mode of ‘let me think about it’ when asked if one may do something). Relatively quiet and reserved, the mental parents caution us in our activities and temper the emotions whilst heaping prohibitions upon the children.

Even when permission is granted (the children or positive commandments gain independence), it is still stipulated with conditions (as parents never leave the scene entirely, just as the positive must remain beholden to the negative). Alternatively, another configuration would be to see how the feminine surrounds the masculine (see Yirmeyahu/Jeremiah (31:21)“…for God has created something new in the earth: a woman will court [literally ‘surround’] a man…[nekeivah t’sovev gever]”) in the sense of how a central presentation or assertion must be circumscribed in a prohibitive sheath–a contextualization of what we do by the envelope of what we cannot do.

In Part Four, our exploration of the masculine and feminine modalities of law will continue.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-organization-of-law-part-4/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-organization-of-law-part-2/

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)