The “Organization” of Law (Part 1)

By Asher Crispe: March 24, 2014: Category Inspirations, Quilt of Translations

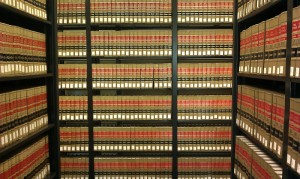

I have grown up in a family of lawyers. My brother is a lawyer. My father is a lawyer. My grandfather and even great grandfather were too. At an early age I would visit what was then my grandfather’s law office and stare at the rows and rows of law books shelved beside his imposing wood desk. You might say that this was my first exposure to the law or at least to the manner in which law was recorded and studied. I recall pulling down an odd volume here and there and attempting to scrutinize the pages.

I have grown up in a family of lawyers. My brother is a lawyer. My father is a lawyer. My grandfather and even great grandfather were too. At an early age I would visit what was then my grandfather’s law office and stare at the rows and rows of law books shelved beside his imposing wood desk. You might say that this was my first exposure to the law or at least to the manner in which law was recorded and studied. I recall pulling down an odd volume here and there and attempting to scrutinize the pages.

The technical and somewhat archaic writing from trials of a bygone era escaped me at a time when I was barely taller than the third or fourth shelf. Nonetheless, I also seem to remember being deeply impressed by the myriad of technical details, parsing of evidence and desire for precision in the wording of documents. My difficulty was reconciling this with my scanning of those black, brown and beige bindings with titles such as American Law Reports which did not yield the slightest sense of how they all fit together. The method to the madness was hidden from me–presumably a well-kept secret for the practitioners that was transmitted only to the attendees of law schools.

As an adult I did not pursue the family profession but I did undertake a course of study in rabbinical law that provided many striking parallels with western law. The vast rabbinic legal literature that I house in my home now greatly outnumbers the number of secular law books that were in my grandfather’s office in my youth. Many of my original questions still linger, only now they span multiple traditions and have awakened an interest in comparative legal systems. At the heart of my curiosity, I am still perplexed by issues of organization. How does it all fit together? How do the various laws complete and complement each other? And, as new cases continually crop up, how does one introduce new material, account for contradictions, display precedence or map the historic character of decisions in such an expansive landscape?

As far as Jewish legal tradition is concerned, the Talmud is the breeding ground from which generations of legal theory as well as legal praxis have sprung. Fertilized by the enduring virility of the Written Torah which supplies the seed passages and verses under consideration, the Talmud acts as the repository for the accompanying Oral Torah (as now preserved in writing) which functions as the feminine counterpart. Each seminal idea undergoes the bulk of its development in the theater of talmudic debate, much like the morphogenesis of the fetus in the womb of the mother. The unique web of tensions spun around any given legal topic can themselves be counted as the fecund matrix material in the production and reproduction of self-sustainable legal procedures and guidelines takes place.

Due to its voluminous size and complex intertextual nature, the Talmud has been aptly characterized by its own expositors as an ocean (yam ha’Talmud). With its constantly shifting waters, this dynamic super-mass of currents and tidal forces is literally teeming with ideas. All of the casework–the hypothetical thought experiments and the real world lessons–surface and submerge, commingle and disperse, in the sea of hyper-intellectual exchange as free-floating signifiers whose correct assignment to actual people, places and events necessitates centuries of super-commentary to properly net.

Is this what properly embodies law? Is it nothing more than an amorphous and unstable series of flows, waves and vortexes? Are we meant to swim in it? It turns out that moving through these waters is first and foremost accomplished with the aid of the ship of the self. The body is itself a skiff. And by the body we do not mean simply the physical body but rather the lived body, the phenomenological body. The fabric of my subjective experience is cast from the incorporation of my sense of immediacy and proximity. I am located in the world but my world begins with my consciousness of the smaller sphere of my locality and positionality which is itself inscribed within the larger bubble of my experiential horizon.

Faced with an oceanic legal system, the system risks becoming an anti-system. One could easily drown. The feeling of being tossed in an ocean can often approximate the nullification of the self back into the awesomeness of the infinite. We have to be able bodied in order to swim unassisted. For us, this implies that we have to maintain some sense of self–not of egotism but of the individual human condition. The parabolic body can ideally float in this ocean because the body is the key organizational principle. On a figurative level the lived body is the basic framework of our lived experience. It is the portable context with which we evaluate everything we come in contact with. Therefore, when it comes to Jewish conceptions of law there is no more privileged metaphor than the human body.

The ‘constitution’ of law is con-figured with reference to our somatic experience. This holds true for the individual as well as for society. The collective (along with its shared experience) has its own embodiment–the social body. In kabbalistic thought, the most basic notion of a system derives from the physical design of a person. An organism has organization, especially the familiar human kind. Particular experiences congeal into distinct organs each with a unique function or set of associate processes. In this way we begin to demonstrate a capacity for compartmentalization, which on a conceptual plane is indexical and categorical. Thus, the systemization of Jewish law–its organization–is determined by or modeled after the body.

Before accessing law (in the sense of the Hebrew term halacha) we first must pass through pre-law by way of the mitzvot or ‘commandments.’ By this we mean a proto-legalistic basis for law, primal instructions which lie underneath and support the fully developed legal system which gets layered on later. If the basic directives are broken down into organs and limbs of the body, then the laws associated with them might be likened to the cells and even organelles. Biology informs legality. It is a living law.

The commandments of the Torah (mitzvot) are referred to as the commandments of the King (mitzvot HaMelech). Divinity expressed as a King is the foundational figure of authority or authority figure (it is important to contemplate both turns of phrase) of a transcendental order. If we think of the commandments as performatives, then their performance is likened to the construction of the ‘body’ of the King–a metaphysical body as the Zohar (II 85b) renders it: “all of the commandments of the Torah are connected with the body of the King…,” to which we might add, that this special set of performatives also unifies our image of sovereignty.

The commandments of the Torah (mitzvot) are referred to as the commandments of the King (mitzvot HaMelech). Divinity expressed as a King is the foundational figure of authority or authority figure (it is important to contemplate both turns of phrase) of a transcendental order. If we think of the commandments as performatives, then their performance is likened to the construction of the ‘body’ of the King–a metaphysical body as the Zohar (II 85b) renders it: “all of the commandments of the Torah are connected with the body of the King…,” to which we might add, that this special set of performatives also unifies our image of sovereignty.

The fully functioning embodiment of the authority can only be realized once all of the component parts are in place. The authoritative body is integral–there are no surplus parts nor may any of them be omitted (just as our biological bodies operate optimally when they are fully constituted). We need a certain level precision construction, orchestrated with care for the fine details, to have an organ functioning properly. So too, in any vital legal system all of the elements of law should be integrated both within themselves and with each other.

Organs are only semi-self contained. They have internal functions and internal communications but they also communicate with the rest of the body. Hence, any set of laws must naturally strive for this type of co-existence and collaborative architecture. A lack of manifest authority is therefore comparable to a missing limb or damaged organ. In this way, the crisis of the part affects the whole. Details matter, especially if we are to maintain compatibility throughout the system.

In Part Two we will investigate further infrastructural features of the body of law where the affirmative and prohibitive meet up.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-organization-of-law-part-2/

The “Organization” of Law (Part 1),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

Not sure of the difference between “figure of authority” and “authority figure”. Please explain your thoughts more in detail. Thanks. Does “figure of authority” mean the entire Divine Personality, whereas “authority figure” means Netzach-Gevura?