The Age of Information and Hyperconnectivity (Part 2)

By Asher Crispe: November 10, 2014: Category Inspirations, Networks of Meaning

For a long time we could believe in the world. It stood firmly before us, confident and unassuming. We never doubted it for a second. Certainly the world exists in its own right with complete self-sufficiency, an objective sphere emancipated from our gaze and indifferent to our probing minds?! Or at least so we thought. From the supreme epistemological hubris of 19th and early 20th century positivistic science and philosophy, a crisis erupted that cut the pedestal right out from under us. Known under various guises ranging from ‘the uncertainty principle,’ to ‘fundamental incompleteness,’ to the all invasive acidity of ‘deconstruction,’ the very independent being of the world has been thrown into question. Foundations have crumbled. Gasping in an unbreathable environment, we are in danger of drowning in the dark. And yet, all of this came somehow in the name of progress and with a feeling of expanded consciousness.

For a long time we could believe in the world. It stood firmly before us, confident and unassuming. We never doubted it for a second. Certainly the world exists in its own right with complete self-sufficiency, an objective sphere emancipated from our gaze and indifferent to our probing minds?! Or at least so we thought. From the supreme epistemological hubris of 19th and early 20th century positivistic science and philosophy, a crisis erupted that cut the pedestal right out from under us. Known under various guises ranging from ‘the uncertainty principle,’ to ‘fundamental incompleteness,’ to the all invasive acidity of ‘deconstruction,’ the very independent being of the world has been thrown into question. Foundations have crumbled. Gasping in an unbreathable environment, we are in danger of drowning in the dark. And yet, all of this came somehow in the name of progress and with a feeling of expanded consciousness.

When the world and the objects that populate it (the signified) become shadowy and circumspect due to their newly embraced probabilistic nature, our senses hearken to a command to fashion for ourselves an ark. We are constructing a vehicle to shelter us from a ontological storm. Turbulent ‘reality’ is enframed in language which restores an inside/outside distinction. Temporary equilibrium ensures. We live on the inside (subjective being) while waiting anxiously for the restoration of the dry land of outside world (objective being). World erodes into word.

Teivah (ark), as we mentioned previously, also means a word. Thus, the Divine commandment to our proposed common ancestor or root soul (Noach/Noah) may be philosophically reinterpreted as a metaphysical imperative to find refuge in language. It is the last hope for us to ensure the persistence of self as in Genesis 6:14 “Make for yourself [emphasis mine] an ark….” Self-preservation, the enduring identity of an separate individual cannot co-exist with a world that is not held at a safe ‘objective’ distance. Once the gap between knower and known collapses with a fatal loss of the distinction, how we can continue to speak of a private “I”?

Only the word (teivah) or more broadly speaking–the ‘signifier’ inserts a spacing where the world can’t manage to do so naturally. We write and speak with pauses, intervals, and interruptions that break up ‘characters.’ So too, our use of language installs and reinforces a grammar for our experience of the world. The destruction of and from the natural world is met with the artifice of language as a reconstruction of reality, that which maintains us in the absence of our pre-diluvian existence and will hopefully return us to a new world in a post-diluvian one. Save the recipe and you will bake your cake again some day.

Containing primarily the self and one’s immediate family (although one’s taxonomy for all of life is along for the ride too when we consider the sets of animals), one is tempted to view the odyssey of the ark–of the word-container–as a kind of privatization of language. As I speak I primarily judge my words as I register them, as I dwell within them. However, the word is not completely sealed in on itself with no information being imported from the outside. A window (tzohar) that God instructs Noach/Noah to add to the design (See in particular Rashi 6:16) supplies light from the outside. The suggestion is that while words float and store life, they also internalize radiation from the world around them. An alternative opinion insists that they also self-generate their own light. Rather than a window, it [the tzohar] is a precious stone that sparkles and produces an internal illumination. Often in Kabbalah, light refers to experience. Consequently, a word with a window on the world would entertain a transcendent source of light-experience informing the inner significance of the word or, alternatively, the precious jewel that some commentators think it is (ibid.) sparkles all on its own as a immanent light-experience which feeds off the life that is already inherent within the ark-word as a kind of bioluminescence.

What an interesting turn around! So long convinced that words are mere subordinates to the world, impoverished representatives with no original content of their own other than what we happen to pour into them, here, the flood flips this evaluation on its head. We become world poor unable to locate the criteria for distinguishing one thing from another as every object loses its composition in the deluge of hyperconnectivity. Our only container (if we are to be self-contained) arises out of our retreating to words of our own construction. The self is housed in language. God (reinforcing the timeless and universal application of this task) tells us to come into the ark, to enter words, to place ourselves in them and to remain there temporarily (as we will soon see, there is also a point of departure, a moving through words to what is beyond them as we finally exit the word-ark).

While this word-ark could about be any word, the Chassidic approach emphasizes how this is ultimately about words of Torah and prayer (tefilah). Regarded as fundamental words, they are hewn from the essential kernel of language, that which makes possible the communion of communication. With them we co-create and transform our world. We place ourselves in them so that they may also enter us. When God instructs Noach/Noah (Genesis 7:1) to “come into the ark, you and your household…” He is calling upon us to get on board with the word(s)–to identify ourselves with them. Often we stand aloof from our words or more distressingly, we do not identify with words of Torah or prayer (if one prefers: theory and praxis as they pertain to a theory of everything and the search for a grand unity).

“Coming” into the ark-word also carries another hidden connotation. In the Jewish mystical tradition, it implies a sexual relationship. Spelling out the implications of this sexualized view of language can itself prove to be extremely fruitful. We don’t simply ‘find’ ourselves within words. We also project or place ourselves within them. Energetically we fertilize the sense of the word with ourselves and our entire household of processions. We become intimate with the word. Language intimacy embarks on an adventure that pulls me along. Becoming deeply attracted and attached to these words, we might think that they are all that is left of the world. Our exorbitant enthusiasm may lock us into the word to the degree that we cannot easily escape it and shed its literal meaning–to once again be ‘carried over’ (the etymology of meta-phor) to the world at large. Educationally, this amounts to thinking through the text in order to get beyond it. Our growth is stymied from never wanting to leave the safety of our original womb of words. Letting our words relate only to themselves (the self-referential) rather than having any real impact on the world, is the pitfall of spending excessive time in the closed quarters of the ark-word. We are intended to be terraqueous. Our voyage in the semantic sea must look to resettle on dry land, to reconnect with a signified and to reclaim an outside objective world.

In his three volume magnum opus Spheres, Peter Sloterdijk (Globes: Spheres II p.237) intuits what is at stake with our diluvian tale:

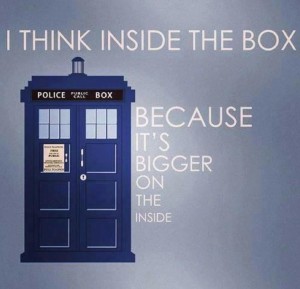

“The ark concept–from the Latin arca, “box” (compare to arcanus, “closed, secret”)–exposes the most spherologically radical spatial idea which humans on the threshold of advanced civilization were able to conceive: that the artificial, sealed inner world can, under certain circumstances, become the only possible environment for its inhabitants.”

For the dreamer who likes rockets, hurling though the vast ocean of space, the sea-sky, the heavens, can only occur if we forge a suitable capsule as our ship. We don’t want to give up our human finitude against the sprawling reaches of that infinite backdrop. Our vessel would be the only thing reminding us of home amidst the great deep. It serves to define our locale. It lets us know that we are here, now (unlike the water currents which stretch from here to there and everywhere in a ill- or un-defined landscape). For Sloterdijk (p.237): “The ark is the autonomous, absolute, context-free house, the building with no neighborhood; it embodies the negation of the environment by the artificial construct in exemplary fashion.” Append to this comment our ongoing rereading of ‘ark’ as a ‘word’ and we should be struck by the connotation for linguistics and semiotics. Perhaps the sign is best described as a signifier immersed and floating in a unstable signified–a water world? But, then, does the sign still get to claim absolution as absolute?

What secrets lurk in the dimensions of the ark? Genesis (6:15) records it as being 300 cubits long, 50 wide and 30 high. Hidden in these measurements is a further allusion to the ark as word. In Hebrew, 30 is designed by the letter Lamed, 300 by the letter Shin and 50 by the letter Nun. Combined, these three letters: Lamed, Shin, Nun, form the root of the word lashon which means ‘tongue’ or ‘language.’ The dimensions of the ark-word are language. This indicates that we measure our words within a standard system of language. They compare and contrast with other words. The whole of language sizes up or constitutes the dimensions of any word and hence, makes the case for a surfeit of intertextuality.

Hyperconnectivity is not merely an internet of things but also of words. Every word is potentially plugged into the entire semiotic grid as a node within the nexus of general linguistic meaning. Road work can always improve the flow of traffic that routes the mind and imagination from word to word. Our ideal word (which is perhaps any word and quite possibility every word) hyperlinks all and all. As a feminine image according to the Zohar, the ark swaps out the womb of mother nature for the matrix of language which we dwell within for we are strangely closer to it. In this way, the word remediates the world.

Additionally, our famed ark-word is Noach’s/Noah’s. What extra scoop of meaning gets heaped upon our interpretation when this ‘brand’ name factors in? Noach/Noah signifies many things, amongst them ‘rest,’ ‘comfort,’ and ‘satisfaction.’ Does his ark then amount to a closed, secret space of respite and consolation? When the old world is destroyed are our lives reduced to pure information? Maybe all we have is our ‘word’? So you might ask: ‘what defines a word?’ No longer can it claim to be anchored to the ground. The ground is gone or at least temporarily obscured. The word can only refer to itself. It must be included in its definition. Circularity is suspect.

Additionally, our famed ark-word is Noach’s/Noah’s. What extra scoop of meaning gets heaped upon our interpretation when this ‘brand’ name factors in? Noach/Noah signifies many things, amongst them ‘rest,’ ‘comfort,’ and ‘satisfaction.’ Does his ark then amount to a closed, secret space of respite and consolation? When the old world is destroyed are our lives reduced to pure information? Maybe all we have is our ‘word’? So you might ask: ‘what defines a word?’ No longer can it claim to be anchored to the ground. The ground is gone or at least temporarily obscured. The word can only refer to itself. It must be included in its definition. Circularity is suspect.

Continuing on Sloterdijk’s train of thought we find that (p.238): “A building can only be absolute by completely decontextualizing itself and clinging to neither landscapes nor adjoining edifices.” How appropriate that the letters of the word teviah (the word for ‘word’) permute in Hebrew to spell habayit (the house). As the classic kabbalistic text on language meditation, Sefer Yetzirah (see the standard commentaries to 4:16) further buttresses this idea by comparing letters to stones and houses (an assembly of stones) to words. A letter is a potential building block of meaning but signification takes up residence in a completed word. Often thought of as a floating house, life on a boat potentially makes us nomadic citizens of nowhere. Before there were semitic wanderings there were semantic wanderings. The super-mobility of the world-flood simultaneously heralds the displacement of everything–a most acute picture of exilic meaning.

We will continue to chisel away at the foundation of the ark-word in Part Three.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-age-of-information-and-hyperconnectivity-part-3/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-age-of-information-and-hyperconnectivity-part-1/

The Age of Information and Hyperconnectivity (Part 2),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

Brilliant.

I once read Sartre’s Nausea, where I believe he became increasingly disgusted by the ‘viscosity’ of his existential view of reality. It seems this is what reality would be without words, there would be only undifferentiated reality, the flood but no ark.

It’s interesting that Noah was instructed to build the ark. Does this mean we ‘make’ differentiation to save ourselves from the overwhelming sea of undifferentiated reality? Maybe some day we won’t need the proverbial ark.