Songs of Myself (Part 8)

By Asher Crispe: September 14, 2014: Category Inspirations, Simple Rhythms

What we have said up until now regarding the musical term zemir (which we introduced in the previous article) does not exhaust the nuances pregnant within this kind of music. One of its most exotic qualities revolves around its role in the formation and augmentation of memories.

What we have said up until now regarding the musical term zemir (which we introduced in the previous article) does not exhaust the nuances pregnant within this kind of music. One of its most exotic qualities revolves around its role in the formation and augmentation of memories.

As we are now heralding the nascent stages of the age of differentiated learning, educators who once found music to be a distraction to serious study (opting instead for the reign of silence over the classroom and in the library) are starting to see its benefits, particularly for certain individuals. Ironically this silence, like John Cage’s 4’33” of silence that we mentioned earlier in Part 4 of our series, is filled with ticks and pops, yawns and grunts, rustling of papers and the sliding of chairs every time we reposition by shifting our weight around.

For those amongst us whose attention resembles a police scanner, we are continually monitoring all channels and frequencies which results in our being driven to distraction. Our mind compulsively sends out an investigator to ascertain the source of the noise–the very same noise that recedes into the pallid surfaces of things for many or most people.

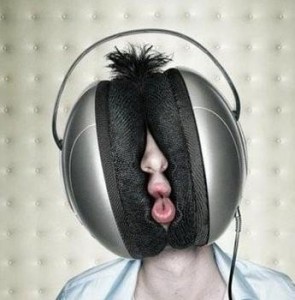

Consequently, the best way to fight the unpreventable and unintended smalls noises that flutter through the silence might paradoxically be with more noise. Similar to noise canceling headphones, the music itself weaves together the auditory stimuli into one familiar garment which we may swaddle our minds with and draw comfort from so as to relax and remain focused. All of this implies a musical experience of gevurah as a ‘restraining’ of consciousness within a fence of music, thus registering it as a cognitive performance-enhancing drug of sorts.

Beyond being a sound filtration system that softens and smooths the din and commotion, music can be thought of as a mnemonic device. Evidence of this can be found in the Talmudic statement of Rabbi Akiva (Sanhedrin 99a-b) who enjoins each and every one of us to “sing every day, sing every day [zamer b’kol yom, zamer b’kol yom]. The notion is that by singing one’s learning one comes to know it with such fluency that it sticks in the mind. Moreover, the sung component of Torah learning represents its most fully developed expression. When we select or discover a new melody by which to actualize our learning, it effectively awakens novel meanings that were latent within the words. It can be the self-same words but set to a different tune. This combination of words and music (and continually altering the music) brings forth untold dimensions of meaning and interpretation.

An additional allusion to this can be unearthed from the Hebrew, “sing each day” or “zamer b’kol yom” for these three words equal 355 when their letters are transposed into numbers. 355 is the numerical value of the word shanah (as in Rosh Hashanah or the new year [literally the head of the year]) which means temporal change or, if you prefer the Derridian construction: to differ and defer. In other words, as time progresses, it is apprehended as a series of changes. Likewise, the word also denotes the idea of repetition. Mishnah, for instance, is not only the name for the teaching of the Oral Law, but also implies those who repeat it. Nonetheless, we are not speaking of the repetition of the same but rather the generation of differences. To playfully paraphrase Plato, ‘you can’t sing the same song twice, you can’t even sing it once’ for it changes from moment to moment [note that for Plato the original quote was about crossing a river rather than a song].

To sing a new song every day is temporalizing our interpretation of the words that we are weaving through memory. While on the surface the doubled expression recorded in the Talmud are identical, in their exposition the commentators bring forth the hidden difference between them. This is true as a general principle of rabbinical exegesis. The indifference riding on the surface camouflages a decided difference underneath. To repeat is to differ. Our daily song replays everything that we have hitherto understood to a new tune that refreshes it.

But why the repetition of the phrase? Why not merely affirm that one should “sing each day”? The most basic reason for the duplication has to do with the comparing and contrasting of this world (olam ha’zeh) with the world to come (olam ha’ba). Loosely speaking, this could boil down to the juxtaposition of the world the way it is versus the way it should be. One song checks up on the would, takes its pulse, tunes into the reality of our present situation, while the other forges ahead striving to redefine the world, to dream, to hope, to harmonize all of the divergent voices.

Delving deeper still, we see that the etymology of the word zemir has a fascinating duality to it. On the one hand it shares a common root with the word tazmir meaning ‘to prune,’ and on the other, it connotes growing branches or zamorah. Grammarians have suggested that it falls into the class of polaric verbs. It is a fusion—a coincidence—of opposites. It either designates the protraction or retraction of branches which are themselves somehow bound up with song.

This oppositional structure is itself present within the word gevurah. While up until now we have only highlighted the sense of self-limitation in this term, there are other instances when it is read as a variation of hitgavrut or ‘overcoming’ (much like a flooded river will tend to overflow its boundaries). Thus, the pruning reflects the first meaning while the second is comparable to the overflowing or extending beyond limits (i.e. the extension or growth of the branches).

Where do we find this in the Torah and how might it be related to memory? While in its simply reading, the prohibition that specifies that “you shall not prune your vineyard [v’charmecha lo tismor]” on the Sabbath (Vayikra / Leviticus 25:4) might seem only to apply to the external agricultural world, its occult meaning reinscribes the activity into the inner dimensions of the soul. A vineyard can symbolize many things but, generally speaking, the fruit of the vine (wine) serves to represent the altering of states of consciousness itself. In similar fashion, the vines themselves are analogous to the neuronet of the brain. A neuron resembles a vine–lots of neurons, a vineyard. Even the dendrites derive from the Greek déndron meaning “tree” (a cherem or “vineyard” in our verse above can also mean a “grove”). Our notion that “neurons that fire together wire together” evokes a sense of growing and connecting new branches or the entangling of vines.

This comparison can also be found in scientific literature whereby we speak of not only the growth of new synapses in the brain but also of our innate ability to effect synapse pruning. A recent study (http://www.kurzweilai.net/children-with-autism-have-extra-synapses-in-brain) has shown that autism may be linked to a reduction in the normal amount of pruning of synapses during childhood development. By generalizing from the root of the word ‘autism’ (as opposed to the medical specifics of the condition), we find that it comes from the Greek autos or “self.” The implication is that if one is too highly self-integrated or linked in, then this may lead to an excessive feeling of being locked in or submerged within the self. Relating so well to the self over-taxes the system resources of our mental processing thereby leaving minimal room for others. Our social space is squeezed by the unpruned vineyard within the mind much like an endless tangle of wires that has become unmanageable.

Our zemir music contains both the capacity to let the branches of memory grow and to trim them back. It manifests both the limiting factors and the potential to go beyond those limits. Excessive or advanced memory capabilities (which are sometimes associated with autism) or even rare cases of hyperthymesia, may result in cognitive difficulties. This is why maturation should include pruning–a process which can be compared to the six days of the week–while the resting and conservation of memory (without information entropy ideally) corresponds to a Sabbath state of “rest” in the soul. Both need to co-operate. We need to edit and revise, grow and develop, but we also require stabilization factors that provide some continuity throughout all of that change. Together these considerations are the marriage of the 6 days of the week with the Sabbath. Moreover, there are weekday songs and there are special songs related to the Sabbath (often referred to as Shabbat zemirot from our term zemir). Perhaps in the future we will discover that the balance of the self in relation to self, versus the self in relation to others (socialization) will be achieved through the power of the right music.

Our zemir music contains both the capacity to let the branches of memory grow and to trim them back. It manifests both the limiting factors and the potential to go beyond those limits. Excessive or advanced memory capabilities (which are sometimes associated with autism) or even rare cases of hyperthymesia, may result in cognitive difficulties. This is why maturation should include pruning–a process which can be compared to the six days of the week–while the resting and conservation of memory (without information entropy ideally) corresponds to a Sabbath state of “rest” in the soul. Both need to co-operate. We need to edit and revise, grow and develop, but we also require stabilization factors that provide some continuity throughout all of that change. Together these considerations are the marriage of the 6 days of the week with the Sabbath. Moreover, there are weekday songs and there are special songs related to the Sabbath (often referred to as Shabbat zemirot from our term zemir). Perhaps in the future we will discover that the balance of the self in relation to self, versus the self in relation to others (socialization) will be achieved through the power of the right music.

We now continue to the most all inclusive term for music–niggun–in Part 9.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/songs-of-myself-part-9/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/songs-of-myself-part-7/

Songs of Myself (Part 8),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)