Songs of Myself (Part 5)

By Asher Crispe: July 23, 2014: Category Inspirations, Simple Rhythms

For all the pleasure in music as an intellectual exercise, we do not listen as decapitated beings. The mind may seek to break free from its tether to the body, but our consciousness is fundamentally embodied; its projections are viewed on the screen of our full somatic stature. When broken down, the simple division of the human figure into mind and body reflects the character of our inner experience. Relative to the body, the head is the seed in its concentrated form while everything else from the neck down follows as an type of exposition or unfolding of the initial idea. Musically speaking, this compares with the compositional method of presenting a theme and variations. Each variation is constructed out of the building blocks and basic materials of the theme but with a different configuration often strained in its resemblance to the original.

For all the pleasure in music as an intellectual exercise, we do not listen as decapitated beings. The mind may seek to break free from its tether to the body, but our consciousness is fundamentally embodied; its projections are viewed on the screen of our full somatic stature. When broken down, the simple division of the human figure into mind and body reflects the character of our inner experience. Relative to the body, the head is the seed in its concentrated form while everything else from the neck down follows as an type of exposition or unfolding of the initial idea. Musically speaking, this compares with the compositional method of presenting a theme and variations. Each variation is constructed out of the building blocks and basic materials of the theme but with a different configuration often strained in its resemblance to the original.

The theme and variation relationship perfectly captures the affinity of pure intellectual intuition and conceptual understanding for one another. As a music axiom or abstract statement, the theme fathers the composition while the variations mother it. Kabbalistically speaking, father (intuition or chochmah) and mother (understanding or binah) remain inextricably linked. Here, the maternal work consists in unpacking and building upon the undeveloped seminal insight and, as with any escapade of opening locked chests and draws and rummaging through old boxes, we are bound to discover something new (or at the very least, to be surprised by something old as though it were new).

Cultivating the music material, turning it over and over, twisting it back on itself, shifting it around this way and that, unearths untold riches and unexpected faces that could not be detected in the initial reception of the starting theme. Binah is depicted as the capacity to understand one thing from out of another (mavin daver m’toch davar) or what we might call derivations (variations) while chochah constitutes the source or origin (theme).

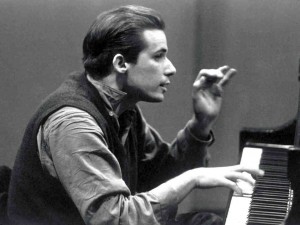

My first real mediation on this musical phenomena (once I had developed a thoughtful and attentive ear) was Johann Sebastian Bach’s (1685-1750) famed Goldberg Variations as performed on the piano by the dazzling hands of Glenn Gould. Without indulging a detailed analysis, we could simply outline it as an opening and closing Aria containing the theme (although some musicologist argue that this itself is a variation of sorts) with 30 variations sandwiched in between.

While no one is suggesting that Bach would know or intend this, it is interesting to point out that the Hebrew word for heart (lev) equals 32 (the number of parts to the composition) and it itself divides into the two letters that spell it as Lamed = 30 and Beit = 2. Likewise, the Torah begins with the letter Beit (in Bereshit [In the beginning]) and ends with a Lamed (of the word Yisroel [Israel]). Sefer Yetzirah (the Book of Formation) further states that the whole of creation is accomplished with 32 pathways of wisdom.

Using our musical analogy, we might now think of them in terms of theme and variation. We apprehend the book ends as a theme which contains within itself a set of variations that build upon it. The letter Beit as a prefix (something fixed in advance) denotes “in” while its name also means a bayit or “house” which can be seen as a frame or context within which the letter Lamed (30 variations) occurs. Lamed as a name suggests both learning and a teacher who provides that learning (limmud and melamed). Thus, the instruction occurs within the construction as structural transformations gestating within the house of the womb which is the contextual main theme.

After our encounter with maskil or intellectual musical experience, there is a need to connect the head to the heart. Even before we reach for full blown emotional energies, we already can distinguish the heart within the mind as compared with the mind within the mind. We might consider the heart within the mind (also known in Kabbalah as the “understanding heart” [binah lieba] as the bridge to the heart within the body. The heart pulsates. It is our internal metronome. We are swept up in the currents of the music. The systole pushes us out of our confinement through a contraction or intensification of emotion and the diastole brings us back in with the resolution of tensions. Of all our synonyms for music, the one that captures this ebb and flow is shir.

Shir carries with it a sense of the fundamental dance that runs back and forth within reflective understanding (binah) itself. Here, binah contains the idea of intermediality or betweenness (bein) within its root. There is a mimetic function to understanding (it does not merely relate to how I grasp the world between me and myself) but rather maintains the splitting of prior seamless experience into subject and object. “I” as the subject (mi or “who,” the subject, emerges and represents understanding at this level according to the Zohar) and it reflects upon the object as something separate from itself. “I” become a mirror which is held up to the world hoping to catch a copy of it indirectly that faithfully reproduces the original thing or experience as it is “out there”. As such, it couples brain and body. “In here” denotes the confines of my mental space where I picture and model the world, while external to the mind, the body serves as the extended substance. I let my mind out into the world by means of my body.

How is this found within the song or shir?

The answer lies in a Chassidic reading or re-reading of a passage from the Talmud (Shabbat Chapter 8, Mishnah 1) where it states that “those [animals] which possess collars are drawn out by the collar and brought back in by the collar.” In the immediate context of its discussion of the laws of Sabbath observance, it would appear to merely be referring to animals which are kept inside (presumably in a barn, corral, pen, or some other enclosed structure that is part of the private domain) yet, on another level, the word for collar (shir) also means “song.” Going through it once more, the implication is that all masters of song (rather than those “possessing a collar”) are released from their pent up, closed spaces into wider pastures for rejuvenation and, once fed from this openness, they/we are led back inside and once again feel contentment with our containment.

Animality in the soul animates us. We yearn to run wild and to be free from our cage. At times this consists of moving from the closed quarters of the mind sealed in on itself (where I can’t get past my own thoughts and risk falling into a solipsistic state) to the breath of the unbounded playing field at large. Music passes us back and forth from our inner world to the outer world, from the immanent to the transcendent domain. It releases us. It gathers us in. The nature of this kind of music pulls us by the neck–the place for affixing the collar. Our animate animal drive pulsates in the juncture that joins the mind (head) and body (feelings). We dance to a tune which takes us out of our bodies (the brain itself can be thought of as an out-of-body experience) and then revives our bodies.

Nowhere do we see this musical potential more potently than in the Song of the Sea (Shirat Ha’yam from Shir) that was sung by Moshe (Moses). In particular, the phrase “az yashir Moshe” [Exodus 15:1] literally means “then Moshe I will sing…”, from which the sages of the Talmud learn that this is textual evidence of the resurrection of the dead in the Torah. It is not only that Moshe sang in the past but that he will once again sing in the future even though he has passed away. But this interpretative line of reason does not end here. Beyond the marvel of the dead coming back to sing some future song, this is also (due to the ambiguity in the original Hebrew) the additional idea that song will itself be what revives the dead.

Certainly almost everyone with a modicum of sensitivity to music has felt its regenerative effects. Feeling mired in depression one moment and our spirit soaring in the next is the result of firing off of a few good chords or postmarking the notes of a magic melody. My body may be led by my head but the truly important thing is that they remain connected. Disconnected they both die. Music has the power to both restore and maintain this connection. It moves me. It gets around me and leads to nourishment while being in the spiritual zone (a Sabbath experience on a psychological plane). Music (sound designed in the right proportion), builds a new body with a new heart with new blood pumping through it. Not only are the ‘hills alive with the sound of music’ but you and I are as well, even if we were already feeling dead. This is the joy of song (noting that joy or simcha is the inner aspect of understanding or binah) which transports me.

Certainly almost everyone with a modicum of sensitivity to music has felt its regenerative effects. Feeling mired in depression one moment and our spirit soaring in the next is the result of firing off of a few good chords or postmarking the notes of a magic melody. My body may be led by my head but the truly important thing is that they remain connected. Disconnected they both die. Music has the power to both restore and maintain this connection. It moves me. It gets around me and leads to nourishment while being in the spiritual zone (a Sabbath experience on a psychological plane). Music (sound designed in the right proportion), builds a new body with a new heart with new blood pumping through it. Not only are the ‘hills alive with the sound of music’ but you and I are as well, even if we were already feeling dead. This is the joy of song (noting that joy or simcha is the inner aspect of understanding or binah) which transports me.

From here we embrace the love song which celebrates the miracle of love in our lives in Part Six.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/songs-of-myself-part-6/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/songs-of-myself-part-4/

Songs of Myself (Part 5),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)