Reconditioning the Bipolar (Part 2)

By Asher Crispe: April 1, 2011: Category Inspirations, Quilt of Translations

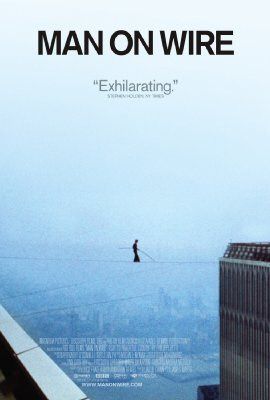

How good is your sense of balance? Just looking at the pictures of high-wire artist Philippe Petit walking on a thin cable 1,368 feet above the ground between the twin towers of the World Trade Center back in 1974 is enough to give anyone vertigo. Clearly this balancing act is in a class of its own. As the subject of a recent award- winning documentary, Man on Wire (2008), Petit has been pushed the envelope over and over with his unimaginable stunts. To maintain one’s composure at such heights with the overwhelming risk of mortal danger seems to be beyond comprehension. It is easy to assume that such daredevils are simple insane. Yet there is an applicable lesson for the rest of us—one that might support us at the outer limits of our psycho-spiritual capacity.

How good is your sense of balance? Just looking at the pictures of high-wire artist Philippe Petit walking on a thin cable 1,368 feet above the ground between the twin towers of the World Trade Center back in 1974 is enough to give anyone vertigo. Clearly this balancing act is in a class of its own. As the subject of a recent award- winning documentary, Man on Wire (2008), Petit has been pushed the envelope over and over with his unimaginable stunts. To maintain one’s composure at such heights with the overwhelming risk of mortal danger seems to be beyond comprehension. It is easy to assume that such daredevils are simple insane. Yet there is an applicable lesson for the rest of us—one that might support us at the outer limits of our psycho-spiritual capacity.

Our well-being often rests on having a well-established center of gravity. Finding our center of gravity practically entails the discovery of the force that helps us to pull ourselves together. ‘Holding it together’ as the expression goes, presents the greatest challenge when faced with extreme situations. With so much at stake, being able to fully commit, being ‘all in’ and placing aside any reservation is no easy task. When we feel inwardly imbalanced then it becomes impossible. Too many forces are pulling us in different directions making it difficult to quickly correct our balance. If anything we often over compensate.

How many times have you gotten into the shower when the water is freezing cold? The standard knee jerk response is to crank the hot water all the way up which of course results in being scaled now that it is too hot. With our skin on fire, we again overdo it and crank the cold back up and the process repeats itself several times until we find a comfortable medium.

This approach would cause most of us to fall off the high wire. Conventional wisdom suggests that one better not climb so high in the first place if there is a chance of falling—particularly when it might result in our breaking something. It is fine to test our limits but we also need a sense of what we can handle. Spiritually climbing to the heights is fine as long as we have an inner sense of peace and are going into the experience with enough self-awareness to stead ourselves. It is also good to know when to climb back down. Controlled descents are obviously preferable to falling.

In offering some guidance for coping with the balancing act of life, various kabbalists have pointed out that Sefer Yetzirah (the Book of Formation) employs the terminology of ‘run and return’ to define the extremes of the psyche whereby the ‘return’ marks the need to stay grounded and not be carried away with the ‘run’ upwards. In Sefer Yetzirah (1:8) we find the cautionary note: “If your heart runs, return…” and here there are three distinct textual variants as to the manner and characterization of the return—to return “backwards”,, to return to “the place” or to return to “the one”.

What is most illuminating about these three textual versions is how they all complement one and other in the commentary tradition.

First, the sense of one’s flight, of soaring into the heavens on a super spiritual, intellectual or emotional high, may cause a person to suddenly recoil in fear. The sense of return that tells us to go back is simply an instinctive impression that we have gone too far to one extreme and that we need a psychological course correction. Maybe we should take things slowly or wind then down a notch? Perhaps we should return back to where we came from originally? It is as if to say, that one should never leave on a perilous journey if one does not know how to find one’s way home again. Don’t buy a one way ticket. Book a return before you ever take off. Alternatively never agree to take off if you have doubts about landing.

First, the sense of one’s flight, of soaring into the heavens on a super spiritual, intellectual or emotional high, may cause a person to suddenly recoil in fear. The sense of return that tells us to go back is simply an instinctive impression that we have gone too far to one extreme and that we need a psychological course correction. Maybe we should take things slowly or wind then down a notch? Perhaps we should return back to where we came from originally? It is as if to say, that one should never leave on a perilous journey if one does not know how to find one’s way home again. Don’t buy a one way ticket. Book a return before you ever take off. Alternatively never agree to take off if you have doubts about landing.

Second—to ‘return to the place’ might as well be read as to ‘return to one’s place.’ At first glance, this might appear to be the equivalent to the first version, however there is an important difference. In the returning back of option one it is an automatic reflex. We are spurred by a gut sense of danger from the run of emotional excitement. One might think: ‘if I let this emotional rush keep going, then I am going to lose control.’ It is like reaching the point of feeling like anywhere but here is better for me because I cannot handle the high intensity of this experience. By contrast, ‘returning to the place’ is a conscious recognition of where I really belong. This may or may not entail returning to my original place.

What is most import is that it be the place where I belong. My time in outer space or up on the mountain is breathtaking and exhilarating while it lasts, but even at high altitude I know that my real calling is to be at home down below. Life in the valley, life with family and friends with all of its everyday socialization is the place to resume true life now that I have been inspired from my emotional run. It may even be by virtue of the run that I merit to find my place.

The Talmudic wisdom deposited in the Ethics of the Fathers (6:6) reflects this notion with the saying “Who is wise? The one who recognizes his place.” Knowing one’s place in life if certainly key to finding balance. Much of the pull of the bipolar condition comes from wanting to be somewhere I don’t belong, playing the part of someone who is not me. Misplaced persons experience alienation.

For a person to run away from an inner sense of being at home—specifically of being at home with one’s self—is to uproot an essential anchor of our personhood. At the same time, the jet propulsion that fuels our running here and there, is engineered and mixed directly from the malaise of homelessness. Of all of the pathologies of the self, one of the most difficult to cope with is the nausea of rootlessness, of the unhomely. Likewise, in the Book of Chronicles (I 16:27), the gift of knowing one’s station in life, being a ‘home owner,’ is expressed as: “…strength and joy in his place.” Being able to ‘place’ myself, acknowledging where I belong, is a source of strength and joy.

Finally, the third option is to ‘return to the one’. The ‘one’ really means the fundamental unity, the sense of oneness. Sometimes we want give up everything we have to go about seeking the unattainable. We are running away from everything that defines us. Our personal profiles suggest that we have a certain resume, a public persona, definite character traits, talents and abilities that ‘contain’ our soul. This is the embodied self. ‘I’ fill all of these containers, these descriptive vessels, the tools and equipment of my intangible being.

But why can’t we remain undefined? Why can’t we go through life undeclared or unaffiliated? Perhaps I am none of these things? Nothing can really contain me. So shouldn’t I leave it all behind and allow my higher self to emerge? Ascending to another level of existence—one of complete unity—I am one with my entire being. I have no parts, no dividing lines. This is the run.

The return, therefore, is totally counterintuitive. The ultimate oneness, the truest self, is found specifically below. Incorporating all of the infinite and inexpressible mystery of my being into the finite containers of this world, into the garb of ideas, the dress of words and the outfits of action, connotes the vital oneness. The balance derives from accepting that I am immanent within the framework of my life below while simultaneous being transcendent to it all.

The return, therefore, is totally counterintuitive. The ultimate oneness, the truest self, is found specifically below. Incorporating all of the infinite and inexpressible mystery of my being into the finite containers of this world, into the garb of ideas, the dress of words and the outfits of action, connotes the vital oneness. The balance derives from accepting that I am immanent within the framework of my life below while simultaneous being transcendent to it all.

There is a symmetry between below and above. Moreover, what is below should aspire to rise up to what is above and what is above should desire to descend to what’s below. The extremes then cancel. Self is evenly distributed between below and above, the highs and the lows. I must accept them as both being me and in doing so find my balance even when dangling on a wire.

Reconditioning the Bipolar (Part 2) ,

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)