Position, Measurement and Observation (Part 1)

By Asher Crispe: August 16, 2013: Category Inspirations, Quilt of Translations

Prologue to a Theory of Law

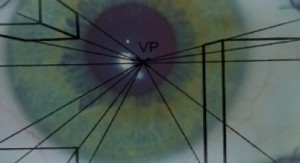

When we look out into the world what do we see? Are the objects within our gaze (or otherwise delivered to the mind via the various senses) residing as they would be in and of themselves in a state of quiet repose? Or does our information gathering activities–our transforming of hitherto unnoticed indefinite things into objects of study in our intention to know them–somehow contaminate the scene?

When we look out into the world what do we see? Are the objects within our gaze (or otherwise delivered to the mind via the various senses) residing as they would be in and of themselves in a state of quiet repose? Or does our information gathering activities–our transforming of hitherto unnoticed indefinite things into objects of study in our intention to know them–somehow contaminate the scene?

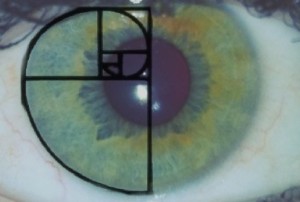

Knowledge also seems to carry with it reflective judgements. We seek definition which tends to cut out our object of investigation from its surroundings in order that such a separation ensure that it be endowed with an identity all its own (an identity that we can recall and wield in the grand scheme of building our systems of thought). Like a tailor sizing up a customer for a new suit, we measure our perceived intelligible objects and attempt to fit them into concepts (subsumption).

Riding along with this description of knowledge comes the premise that there is a correct size in the first place. We either uncover it accurately or we will fashion an ill-fitting suit. However, with the advent of the most successful scientific revolution to date–that of Quantum Mechanics–this assumption has been revisited with an unprecedented skepticism.

Measurement is ultimately to blame. Now, more than ever, we are obliged to maintain a healthy degree of suspicion when it comes to any and all ‘standards’ of measurement. Experimental evidence has emerged from the micro-world that suggests that objects are not passively turning themselves over to be known. Like a fugitive, they squirm and struggle to evade capture. Arresting them and transporting them back to the holding cell of the mind proves to be the greatest of challenges especially when you want to ‘bring them back alive’ and unharmed. In short, we disturb everything we look at or touch. Not to suggest that measurement has degenerated into a futile exercise but rather that its sterling credit rating has been significantly downgraded.

Hard measurements are likely to ‘break’ the object in question. By contrast, soft measurement (a kind of ‘measuring without [really] measuring’) might preserve more of the object’s ‘original nature’ but our involvement mixes in even when it is not wanted despite our attempts to limit ‘exposure.’ This ‘Quantum’ view of reality underscores our role as co-creators of the world at large. Rather than simply having lingered in a state of not being known, things, at least in part, acquire qualities that may not have existed before.

Yet, we need not look solely to the progress of the modern age for the development of such a critique of knowledge. Already, ancient Jewish sources have put forth countless examples of the ‘head strong’ case for boundless knowledge acquisition being dampened by a ‘black velvet yamaka’ as a reminder of all that eludes capture or remains outside of our field of view. It is a delicate state of unknowing that circumscribes the head of the agent intellect whose minimal weight and suggestive opacity retains a blind spot at the apex of the mind.

How do these questions of scientific measure translate into the realm of law? How do they inform a theory of judgement? What is judgement as ‘measuring’ of a case in relation to law? Is it also a measuring of law?

We can detect all of these concerns within the confines of a single verse from the book of Habakkuk (3:6) whereby we may interrogate the questions (somewhat like ‘questioning the questions’ only cruder) of position, measurement and observation in relation to law. This verse reads as follows:

“He stood and measured out the land; He looked and dispersed nations. Everlasting mountains were smashed, eternal hills were laid low; for the ways of the world are His.”

Following the well known statement of Jacques Derrida in his essay ‘Force of Law: The Mystical Foundation of Authority’ that “deconstruction is justice” [Acts of Religion p. 243] we can minimally assert that the process of deconstructing a text is an attempt to justify an interpretation of its meaning. This purports to be more than a careful reading. The need to explain myself to others in the act of reading and to weigh the significance of what is written right down to the letters and words necessitates a delay in judgement. Why be slow to judge unless one is apprehensive about the conclusions to be drawn (how they will re-mark the text itself and make an impression upon all who witness this reading as an interpretive act)?

Reading in slow motion, we can tiptoe through the verse under consideration piece by piece and then assemble it into a larger movement as a reconstituted whole. We begin by asking: Who is “He”? The prophetic vision aims to tell us something about Divine Judgement. If one prefers to de-theologize the expression in order to bring to the fore its philosophic content, we might say the Divine Judgement is judgement elevated to a state of universality. It is meta-judgement. A superlative articulation of judgement that all created beings (most especially the human) aim to emulate. Since the essential Divine name-identity is referred to as Havayah (Being or Reality), it follows that Divine Judgement reflects a fundamental structure of Being–the ontological–while our approximation of that ultimate sense is an ontic manifestation (that which pertains to a being, a particular being but not Being in general).

What then is the relevance of God standing [“He stood”]? Does this imply that there are times when God is sitting or in a non-standing position? Furthermore, how can positionality play into it? Is it not a central tenant of Jewish belief that God is non-corporeal? In order to address this issue we may turn to Maimonides’ (Rambam’s) famed 12th century work The Guide for the Perplexed [Chapter 15] where he deciphers the metaphoric aspect of standing (just one of the many terms which misleadingly suggest Divine corporeality or spatiality). There he writes that the operative significance of ‘standing’ is a state of ‘permanence and consistency.’

Normally we would be tempted to contrast this to a state of walking which would imply ‘Being’-on-the-move or ‘be’-coming—dynamic process and change—and, while it may mean all of that, we see another viable alternative in the commentary on the verse by the Malbim (R’ Meir Leibush ben Jehiel Wisser 1809-1879) who asserted that this expression is intended to emphasize a shift in the mode of Divine revelation within history. Quite simply, there are times when God ‘sits’ in judgement (on a chair or throne as an earthly king might) and at others He is ‘standing.’

‘Sitting’ refers to a mode of Being which is (voluntarily) confined and implicated (folded-in). Nature or natural law takes on this quality. The unlimited aspect of Divinity becomes concealed with the veil of the natural world and as a result we only experience a limited amount of Divine self-expression. This sets up boundary conditions for the world. Even our rational faculties becomes restricted to a form of ‘bounded rationality.’ Judgement limits and is limited by this purposeful concealment of infinities (we might even consider how mathematicians and scientists love to tame numbers–infinities and singularities must be canceled, dropped or avoided in the equations that define that natural world, otherwise we face unmanageable absurdities).

For the Malbim, ‘standing’ then implies a transcending of the natural order or a move into a fully extended expression of ‘Being’ or God that is unshackled from the laws of nature. More extensive Divine revelations are evident in the world which are registered as disruptions to its normal working order. Additionally, the seated position was on a kissai (throne, chair) which is etymologically related to the word kasa meaning to ‘cover’ or ‘conceal.’ Unlimited judgements (judgements not limited to the natural order of things, natural law, bounded-rationality, etc…) are concealed within nature itself. It’s not a question of them existing but rather if they’re appearing. They are restrained from ‘standing out’ temporarily.

Now to make further sense of this we will have to work the distinction between an infinite judgement and what is presumably a finite one. To accomplish this, we might view a finite judgement as something which is existing already in advance on the basis of what appears in the world. All I am doing is working within the bounds of what already seems to exist. The real world–one that exists independent of me (or at least pretends to) may have fixed and finite qualities and measurements to its objects (people, places, things and even experiences). In my act of measuring them in order to bring about some form of definition and judgement, I assume that they already are the way they are before I arrive on the scene or meddle in their affairs. In this setup, I only discover what’s there.

By contrast, the infinite judgement escapes the ‘positionality’ of the observer (I am no longer consigned to view reality from a limited perspective whether that be a spacial vantage point or from my own situatedness within my subjective experience) as well as the inert or static quality of the observed. As with quantum theory, there might not be anything to measure before the act of measurement, the object has not yet coalesced into a definitive state but remains nothing (no-thing) or no definite thing. I create for it a garment within which I dress it up in attempting to measure it. Infinite judgements are created (miraculously) from out of nothing. All of the permanence of the objective world dissolves into a playful gesture that interacts with the inner subjective sphere.

Now compare this with the genesis of the word ‘standard’ in english. It is a compound of ‘standing’ and ‘hard.’ In this sense, to ‘stand in judgement’ would be the adoption of fixed positionality. In Hebrew we can also find this connection in that omed, ‘to stand,’ relates to emda or ‘attitude’ or ‘position.’ Clearly we are speaking of finite ‘under-standing,’ then we mean adopting a position or taking a stance on something. But when this terminology is transferred to the Divine (as in our case with the Meta-judgements or ultimate ‘Being’ of judgement) then it works differently. Incorporeal Being (without the limits of a body) is positioned everywhere. We are speaking of the omnipresent whose place is the radical absence of place (a ‘utopia’ from u-topos meaning non-place)–a proverbial ‘view from nowhere.’

In this exceptional form of judgement, being seated (perhaps we should say ‘Being’-seated?) places the placeless, situates the unsituated. More to the point, it is an artificial fitting into place or Self-limitation–God cloaked in the finite world, playing by the self-imposed rules of nature. Seated-ness intimates a sunken in form of Divine manifestation (teva or ‘nature’ in Hebrew also means tava or ‘to drown’ i.e. we are ‘sunk in’ and immersed in the world) or withdrawn into oneself, a self intensification (as one who tenses a muscle in attempting to hold it still). Hence our manner of being is not to just generically ‘be’ but to find ourselves always already ‘being-in-the-world’ in Heideggarian parlance. We are enclosed in a sphere that makes us judge from an insider perspective (from being-in-the-world, whatever ‘world’ carries with it as far as confinement), whereas, Divine judgement can stand out from the world, breach the confinement and view things from inside and outside of bounds.

In this exceptional form of judgement, being seated (perhaps we should say ‘Being’-seated?) places the placeless, situates the unsituated. More to the point, it is an artificial fitting into place or Self-limitation–God cloaked in the finite world, playing by the self-imposed rules of nature. Seated-ness intimates a sunken in form of Divine manifestation (teva or ‘nature’ in Hebrew also means tava or ‘to drown’ i.e. we are ‘sunk in’ and immersed in the world) or withdrawn into oneself, a self intensification (as one who tenses a muscle in attempting to hold it still). Hence our manner of being is not to just generically ‘be’ but to find ourselves always already ‘being-in-the-world’ in Heideggarian parlance. We are enclosed in a sphere that makes us judge from an insider perspective (from being-in-the-world, whatever ‘world’ carries with it as far as confinement), whereas, Divine judgement can stand out from the world, breach the confinement and view things from inside and outside of bounds.

Would this then not indicate that the expression ‘He stands’ introduces a Being-beyond-nature or an ‘unnatural’ state of Being? Would it nullify nature or strip nature of its professed privilege of mediating all judgement, or having the final say? Would the ‘last’ judgement (in the sense of the ‘end’ and ‘aim’ of judgement) always be super-natural?

In Part Two, we will examine how the restoration of this ‘pre-positional position’ that judges all judgements effects a new kind of ‘open’ or ‘creative’ measurement.

Position, Measurement and Observation (Part 1),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)