Lost (and Found) in Translation

By Asher Crispe: February 18, 2011: Category Decoding the Tradition, Inspirations

There is a story of the universe being a book that was created from out of another book. Both books are described as Torah. What a perfect mirror, what a polished lens—delving into them might bring us to inspired places. Yet we struggle. Proceeding by fits and starts, the standard practice of reading is often met with mixed success. We are looking for relevance but relevance is hard to find when we can’t always see ourselves or today’s world or that elusive ghost called reality reflected in this mirror.

There is a story of the universe being a book that was created from out of another book. Both books are described as Torah. What a perfect mirror, what a polished lens—delving into them might bring us to inspired places. Yet we struggle. Proceeding by fits and starts, the standard practice of reading is often met with mixed success. We are looking for relevance but relevance is hard to find when we can’t always see ourselves or today’s world or that elusive ghost called reality reflected in this mirror.

Could it be that we cannot tap into the original because the pass codes have been changed? The means of accessing these ancient texts stem from the success of translation. As a decryption key, the translations have to be constantly updated or else we are barred from entering. Reading the translations of earlier generations can speak across time but it does not satisfy the demands of the present generation. A new voice must be added—as the Sages of the Talmud insist that a person must regard today as the day of first receiving the Torah. In short, keep it current or lose it.

One of the most intriguing statements of the Talmud suggests that the Torah, despite all of its inner perfection, is not complete until it has been translated into the 70 languages of the world. The art of this polyglot translation relies less on the knowledge of national dialects than it does on recognizing that the Arts and Sciences comprise the “conceptual” languages of the world.

What do those who formulate their understanding of the world in the idiom of economics or politics have to communicate to those for whom film and literature, mathematics and psychology shape their perception of life? Likewise, how is a person to relate to Judaism and find meaning and relevance between apparently archaic history and laws, and his or her day to day routine?

Moreover, the passionate pursuit of a host disciplines, each with a language particular to it, has effectively isolated many in their own field of specialization. Today, with the cultural climate that saturates the mindset of each and every one of us, merely acquiring the Hebrew language and skills of reading the cannon of texts that classically define the historical approach of ‘classical’ education is not enough.

Something is still lost in translation. The inability to speak to the creative and intellectual interests of the majority of the contemporary world from out of the tradition of Torah wisdom is not due to its lacking in content. Rather, we have neglected to sufficiently define the questions that fascinate and drive the modern world in terms of the unparalleled insights of Torah. New innovative translations, in response to the all-too-common disconnect between our experience world of today and dated translation, hold the promise of reversing our perceived senescence of the text.

Emphasizing the mandate to communicate the meaning of the Torah, Jewish tradition has evolved the practice of a threefold reading technique designed to ensure the enduring life of the Book of books. This custom is known by the acronym shemot which stands for shnayim mikra v’echad targum: two times (reading the Torah) original and once (reading) the translation. As a result of observing this practice, the Sages say a person will merit long life.

Emphasizing the mandate to communicate the meaning of the Torah, Jewish tradition has evolved the practice of a threefold reading technique designed to ensure the enduring life of the Book of books. This custom is known by the acronym shemot which stands for shnayim mikra v’echad targum: two times (reading the Torah) original and once (reading) the translation. As a result of observing this practice, the Sages say a person will merit long life.

Questions abound. Why would longevity be linked to a practice of multiple readings? Why the double reading of the original text of the Torah? Why the mandate to include the translation as one of the essential readings, especially in a case where a person might be fluent in the Hebrew of the original?

For starters, we have to ask after the nature of this book. We might define it as an issue of the life of the book rather than the life of the reader. This manner of reading might be an attempt at the radical life extension of the life of the book. Books that speak to us are alive. Books that fails to speak to us are dead. If we want this book to live and be relevant then it will require this strange threefold form of reading. But that’s not all. This body of text is also the text of the body, of the world—the life of the book turns into the Book of Life according to the mystics. So the better versed we are with reading and translating it—like the decoding of the human genome—the better will be the resulting technology with which the life of reader can be extended.

Ruminating on the doubling of the reading of the original text, the great 16th century rabbinical giant known as the Maharal of Prague, in his work Tiferet Yisrael, breaks down the issue into a question of where, amongst the three readings, does the translation occur.

The simple and obvious explanation could be that when we first experience the book in its original language, we have nothing to adequately contrast it with. Then, when encountering the translation, we are running into an interpretation. Translation is commentary. It displaces the original while providing the basis of a comparison. With this, our ‘original‘ understanding is altered. When we subsequently revisit the original text for the post-translation third reading, our perception of it has been modified. It is no longer the ‘same’ text, or rather it is both the same (the identical letters and words) and somehow different (due to our mutated consciousness of it).

Another possibility is that the two readings of the original reflect the inner and outer dimensions of the Torah itself. The inner dimension represents the esoteric playground of the Kabbalists, the soul or inner animating meaning of the Torah. By contrast, the outer dimension, or revealed body of the Torah, addresses the concrete concerns of Jewish law and historicity. These two partner in a dance that leaves faint impressions upon the third reading which is the translation. In this configuration of readings, the translation is the lowest level and denotes a diminished sense of the two higher readings of the original.

A third and most remarkable possibility places the translation on the top level, surpassing the scope of the original. This twist of logic, in a certain way, paints the original as only existing for the sake of the translation. While this world was created for and from the language of the original text, the Maharal contends that the translation belongs to the future world to come. Meaning is confined in the original but liberated in translation. Translation is transformative. It extends and enriches the meaning of the original. It speaks to the outside.

A third and most remarkable possibility places the translation on the top level, surpassing the scope of the original. This twist of logic, in a certain way, paints the original as only existing for the sake of the translation. While this world was created for and from the language of the original text, the Maharal contends that the translation belongs to the future world to come. Meaning is confined in the original but liberated in translation. Translation is transformative. It extends and enriches the meaning of the original. It speaks to the outside.

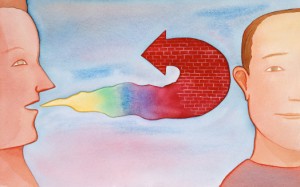

The limits of reading both the revealed and concealed dimensions of the Torah in the original have to do with a language which remains closed in on itself. Some have called this an in-house language. Speaking to a crowd of insiders, of like-minded individuals initiated into the source language, may suffice in the ethereal realms but it does not reach beyond, nor does it speak to the other. It certainly does not penetrate into the lower worlds.

One of the most fundamental teachings of Kabbalah is that each of the commandments and practices of the Torah have a universal application across time and space. This is not to say that the plain meaning of these commandments is always pertinent at the level of action. Rather, they may be applicable to the levels of thought and speech. In line with this teaching—remaining up in the air and disconnected—the readers of this original language risk transgressing the Torah’s prohibition against incest in the abstract at the level of speech.

Incestuous discourse is epitomized as the insistence of marrying only amongst the same pre-established family of concepts and expressions, employing words of kindred spirit. Speaking to the other in the language of the other is the power of true translation. The prosperity of meaning calls for the establishment of new relationships and channels of communication, disseminating and forging unions beyond one’s comfort zone.

For this reason, the translation belongs to and even helps to constitute the future world to come. In Hebrew, olam haba, the world to come, has another striking implication. The word “to come”, haba relates to the beya (coming) as a continuous process. It is also a euphemism for sexual relations in rabbinic writings. Abstractly, it implies a world that is a process of continuously generated creative connections, a network of interconnectivity. Finding everything available in virtually endless varieties of translation, positions “translation” itself as the future. While the internal self-referencing of the original entails arrested development on some level, the translation provides growth and transcendence.

In his commentary on the Ethics of the Fathers (5:21), the Maharal, provides an amazing insight into the words of Ben Bag Bag who says: “Learn it and learn it (the Torah), for everything is in it.” The expression “learn it and learn it” is expressed in Hebrew as “hafak bah v’hafak” which literally means to “turn it and to turn it.” A trope in Greek comes from the word tropos which means a turn. Trope refers to the use of figurative language in a literary context. Thus, the expression to “turn it and turn it” could be interpreted as a need for a tropological reading of both the esoteric and exoteric strata of the Torah text.

Following this, the final part of the statement “for everything is in it” actually shifts from Hebrew to Aramaic (which is the classical ancient language of translation): “d’chola bah.” Why change languages from the original Hebrew to Aramaic within a single expression of this Sage? The Marahal explains that this was in order to allude to the threefold reading practice of twice in the original text of the Torah (the two turns or tropes of the source language) and then the one time in translation (here Aramaic, which was once the readily understood language of the common person back in the day).

Astonishingly, the Marahal purports that “everything is in it” is in translation because it is the reading in translation that specifically captures the connectivity and ‘relatability’ to demonstrate how “everything is in it.” The original is enriched by the translation to the extent that we will be able to open the original text to the whole world and aid the whole world to find itself in the original. The translation here acts as a palimpsest that permits the overwriting of the original. The original would appear to be lost in translation but it is in fact recovered. The recovery of the original through translation is a paradoxical finding by covering over again: to re-cover. Thus meaning of the original is not only lost in translation—it is also found in translation.

Astonishingly, the Marahal purports that “everything is in it” is in translation because it is the reading in translation that specifically captures the connectivity and ‘relatability’ to demonstrate how “everything is in it.” The original is enriched by the translation to the extent that we will be able to open the original text to the whole world and aid the whole world to find itself in the original. The translation here acts as a palimpsest that permits the overwriting of the original. The original would appear to be lost in translation but it is in fact recovered. The recovery of the original through translation is a paradoxical finding by covering over again: to re-cover. Thus meaning of the original is not only lost in translation—it is also found in translation.

The courage to pursue this course with radically innovative translations that captivate and contain the whole world, may be found in the curious figure in the Talmud known as Rabbi Chutzpeet hameturgaman. He is his name. Rabbi Chutzpeet is an interpreter, hameturgaman specifically means a “translator”. What sort of translator? Chutzpeet is a veiled allusion to the word chutzpah which means “emboldened” or “audacious”. Today, we must demand translators who are willing to take the risk and provide bold translations.

Awaiting the fullness of a novel translation, we must overcome the obstacles of translations that are excessively weighted down by the gravity of the original standing posed between sterility and incest. While there is certainly a time to delight in the endless internal reverberations of the original—to indulge an appetite for illuminating the self-references within the text of the Torah—ultimately we must participate in a completely interconnected world and give birth to the new meaning of today. We are obligated to breathe new life into ancient books.

In his seminal essay on The Task of the Translator, Walter Benjamin faces the challenges head on. By entertaining ideas on the limits of representation and the ‘foreignness’ of language itself, he places the stakes as follows:

Translation is so far removed from being the sterile question of two dead languages, that of all literary forms it is the one charged with the special mission of watching over the maturing process of the original language and the birth pangs of its own.

We can and must present the case for the singularity of our times and embroider the traditional texts of Jewish tradition with new translations, conversant with the contemporary languages that link the people of today with the wisdom of yesterday and the promise of tomorrow. Then the book may be able to bind our lives just as it is bound by our lives. No longer a lost book that is nowhere to be found, the text transposed becomes a book which is found everywhere.

We can and must present the case for the singularity of our times and embroider the traditional texts of Jewish tradition with new translations, conversant with the contemporary languages that link the people of today with the wisdom of yesterday and the promise of tomorrow. Then the book may be able to bind our lives just as it is bound by our lives. No longer a lost book that is nowhere to be found, the text transposed becomes a book which is found everywhere.

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

Some Yichudim:

• In theory, the Ramabam holds that a Sefer Torah may be written in ancient Greek letters.

• The Jewish custom of never really speaking Lashon Hakodesh in conversation, but instead always adapting a yiddish or ladino or even israelite aramaic. So the Hebrew text is always being studied “in translation.” The act of translation giving you that elevated distance to respect and analyze each word and letter. And then having to bring it over into your daily language. Like the word itself “translation,” from “trans” “fero” meaning “to carry across” – like Yaakov trying to carry the vessels across the river, wrestling on one side before confronting on the other.

• As I understand, Islam maintains that the holiness of the Koran does not extend into translations. That the translation of the Koran is not the Koran. Which seems to be a denial of the very ability to translate at all. While according to some scholars, the Christian gospels themselves are actually a translation of an older lost aramaic original. To me, these differing approaches to translation express something of the nature of these western traditions as a whole.

I end up meditating on the very act of translation.

and then I arrive at the thought that everything,

absolutely everything is in truth a translation.

Our experience of life is a translation of the utterly ineffable totality,

of what is actually going on.