It’s all about that Balance: Eshet Chayil (Part 13)

By Sara Esther Crispe: March 16, 2015: Category Decoding the Tradition, Inspirations

דרשה צמר ופשתים ותעש בחפץ כפי’ה

“She seeks out wool and flax and works willingly with her hands”

It might sound like great parenting to say that we always want a soft and calm approach with our children. But what happens when that child is running towards the street with cars approaching? A loud scream will catch attention and hopefully scare the child into stopping. It is not the way we want to consistently interact with our children but there is that time and place for everything. And that scream is as loving in that situation as a calm voice is in another. Both are motivated by what is best for the child.

Regardless of the situation, being balanced in our approach is essential. There are times we come from a place of lovingkindness (wool) and other times a stricter, harsher approach (flax) is necessary. Then there are the times both can and must be used. The trick is figuring out which is the right one and then ensuring that we remain flexible to switching as necessary.

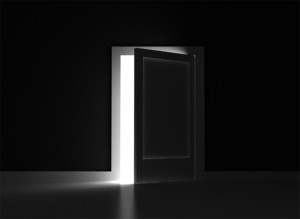

The letter beginning this verse, which focuses on differentiation and balance, is the fourth letter in the Hebrew alphabet, the Dalet. As every letter is also a word, Dalet can be read as delet meaning ‘door.’ A door can be opened or closed. It can allow people in, it can shut people out and we can either enter or exit. The function of the door remains the same. The purpose is what shifts based on what is needed. And once again, there are times that the right thing is to have an open door, and other times when privacy and protection is paramount and the door is not only shut but bolted.

Jewish law instructs that on each doorway a mezuzah be affixed which is a scroll containing the foundational prayer of the Shema. The mezuzah offers protection to the home and is the reminder as well, as we enter and exit into various domains, that there is Something greater than ourselves watching over us.

The text of the Shema begins with the phrase declaring that there is one Creator (“Hear O’ Israel the Lord is G-d, the Lord is One”). In the Torah, the letters appear to be in standard size for the most part, but there is one time each letter can be found enlarged and one time it is found significantly smaller than the other letters. There is great meaning in why each letters is different in each case, and the Torah itself begins with the letter Beit in large form. In the one opening verse of the Shema it is unusual that there are two letters that are found in their enlarged forms, the Ayin which ends the first word ‘Shema,’ and the Dalet which ends the last word ‘echad.’

Those two letters together, the Ayin and the Dalet, spell the word ‘eid’ which means ‘witness.’ The commentaries explain that they are large as when we say Shema we are witness to the oneness or unity of the Creator. There are numerous times in Jewish law that witnesses are needed, but to have kosher witnesses, there must be at least two people who are not related. Now, as stated before, each letter is also a word. So just like the letter Dalet means ‘door’, so the letter Ayin means ‘eye.’ As Dalet is numerically equivalent to four, the word itself for witness can be understood as needing “four eyes” (i.e. two people).

Jewish mysticism teaches us that our two eyes are representative of the very same qualities discussed in this verse (and expounded upon in Part 11), those of chesed, ‘lovingkindness’ (the right eye) and gevurah ‘rigidity’ or ‘strength’ (the left eye). For us to see things in a balanced way, both eyes need to be working properly. There needs to be that balance. When there isn’t, we see things in a limited way. When it comes to being witness however, we need more than just our perspective, so then we are required to have two sets of eyes. No matter how well our eyes are working, we can only see so much at a time. Before passing judgement or coming to a conclusion, we always should try to see the situation through someone else’s eyes.

Furthermore, there is the concept that the feminine has a more dominant aspect of the strength and rigidity when looking at situations than the masculine who is more likely to overlook flaws and see things in a more positive light. Clearly both have an advantage and a disadvantage. It is when both perspectives are combined that we can soften the criticism and likewise not fail to miss concerns and issues that need to be reviewed. In the second verse that begins with the letter Beit it was discussed how the number two is that of connection to another, which is the purpose of creation (and the reason the Torah begins with a Beit.) This idea is then doubled with the number four and represents the idea of a family. While families come in all shapes and sizes, there is the concept of there being a husband, a wife, a son and a daughter. (Not to in any way imply that a family of all daughters or all sons or without children at all is not a “complete” family).

From a spiritual / psychological understanding, the idea is that the balance of masculine and feminine, chesed and gevurah, wool and flax, should be combined within the couple and should then continue to the next generation. Just as the holy garments are allowed to have the combination of wool and flax which would otherwise be forbidden, so too a family is holy and it is in that environment that the mixing should take place and the balance is essential.

We see this balance in a variety of aspects that are all related to four in addition to this foundational family model. There are the four worlds that are taught in Kabbalah that the world was created through. There are the four sons that we read about in the Haggadah at Passover. These four sons are seemingly so different and unrelated and yet all four are necessary components of this family. There is the wise son, the wicked son, the simple son and the one that doesn’t know how to ask. To just whet your appetite as to the depth within, the letters beginning these four sons are a Chet, a Reish, a Vav and a Taf which spell the word ‘cheirut’ meaning ‘freedom.’ Freedom is the result of unifying and connecting with those very different from us. Those who view the world with different eyes.

Along these lines the word for community, ‘tzibur’ is also comprised of four letters relating to four different types of people: the Tzaddik (righteous), the Beinoni (the intermediate), the Vav (the letter of connection tying them all together) and the Rasha (wicked, and same name as is given to one of the four sons). All four are essential parts of society and to be a healthy community we need to engage with and recognize that all are part of this completed whole. Related to Passover as well we have the Four Questions that are recited which relate to four existential ways of viewing our reality and Creation. We then have the four matriarchs (one of which is the woman related to in this verse, Leah). And ultimately we have the four letters that comprise the essential name of God, which is pronounced differently than it is spelled, but is spelled with a Yud, a Hei a Vav and a Hei. This name is known as Shem Havayah meaning the name of existence, and the letters can be permuted to spell the words for ‘past,’ ‘present,’ and ‘future’ (haya, hoveh, and yehiyeh).

Along these lines the word for community, ‘tzibur’ is also comprised of four letters relating to four different types of people: the Tzaddik (righteous), the Beinoni (the intermediate), the Vav (the letter of connection tying them all together) and the Rasha (wicked, and same name as is given to one of the four sons). All four are essential parts of society and to be a healthy community we need to engage with and recognize that all are part of this completed whole. Related to Passover as well we have the Four Questions that are recited which relate to four existential ways of viewing our reality and Creation. We then have the four matriarchs (one of which is the woman related to in this verse, Leah). And ultimately we have the four letters that comprise the essential name of God, which is pronounced differently than it is spelled, but is spelled with a Yud, a Hei a Vav and a Hei. This name is known as Shem Havayah meaning the name of existence, and the letters can be permuted to spell the words for ‘past,’ ‘present,’ and ‘future’ (haya, hoveh, and yehiyeh).

There are those who are continuously stuck in the past, others who are so cemented in the present that they are never looking towards the future and others who only think about what will be that they never really appreciate what is or learn from what was. There must be that healthy balance. And we need to look at ourselves and our lives, with both eyes, and even more so, through the eyes of another as well. Because what we see is limited but when we connect and allow others to also see in, our potential and ability can be revealed in ways that we have overlooked ourselves.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/leah-and-her-unexpected-strength-eshet-chayil-part-12/

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)