Inspiring Interior Design (Part 12)

By Asher Crispe: August 21, 2012: Category Inspirations, Quilt of Translations

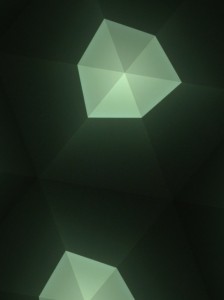

The Play of Light and Shadow

The interior designer who paints with light must also become well aquatinted with darkness. Just as manufacturing uses a combination of additive and subtractive processes to generate a desired object, so too the arrangement of lights establishes both positive and negative space. Light and shadow partner to punctuate our sense of place, revealing and concealing the contours of our interior and the objects that populate it. Consider the active placement of partitions, lamps and window shades, drapes and curtains, and the potency of evoking the privation of light as an essential tool in the designer’s toolkit becomes evident. Darkness informs space as much as light.

If we are to comprehend the unique role of darkness in providing the rhythm and beat in the dance of lights, then we must excavate the Torah’s multi-layered sense of darkness as both a physical and spiritual phenomenon. In order to accomplish this, let us travel back to the crucial passage of interior lighting design of the world-body-home on day one in the Genesis narrative. This time we will quote the passage again with the entirety of the text related to day one, with all of the appearances of darkness and light italicized and numbered (Genesis 1:1-5):

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was chaotic and void, and (1) darkness was upon the face of the abyss. And God said: ‘Let there be (2) light.’ And there was (3) light. And God saw the (4) light, that it was good; and God divided the (5) light from the (6) darkness. And God called the (7) light Day, and the (8) darkness He called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day.”

Our first day of creation may be likened to a ‘reading room’ within which we have carefully positioned ‘accent lights’ in order to bring to the fore the fact that there are eight total manifestations of light and darkness. While our previous reading only entertained the significance of the five instances of ‘light’ by themselves, we will now enter into consideration the three times that ‘darkness’ shows up. A structural analysis reveals that the ratio of appearances of dark to light is 3:5. This relationship brings to mind one of the most important mathematical series in all of aesthetic and design theory: the Fibonacci numbers (which in turn generate Golden Section geometry amongst other things). The cosmos, from DNA to the Milky Way, exhibits this structure. It is unquestionably favored by the Creator given how prevalent it is throughout the Torah and in Creation.

The Fibonacci series works as follows: the first two numbers are like the ‘father’ and ‘mother’ which give birth to (i.e. generate) the third number in the series. Then this number becomes the new mother and the old mother becomes the new father as the process repeats over and over again. Therefore, the series looks like this: 1,1,2,3,5,8,13 or 1+1 = 2, 1+2 = 3, 2+3 = 5, 3+5 = 8 and so on. Taking this back to our passage above, we have three numbers in a row from this series: 3 (times darkness) and 5 (times light) for a total of 8 appearances. And since this is the day of unity (‘one day’), where darkness and light together comprise that time period, we can expose even more allusions to the Fibonacci series such as the fact that echad or ‘one’ as in ‘one day’ (the very last word of the five verses dedicated to this day) equals thirteen. Moreover verse 1:5 (which contains this expression) has exactly thirteen Hebrew words in it. This counts as a wonderful example of self-reference within Kabbalah in that 13 is the next number after 3,5,8 (1,1,2,3,5,8,13 etc…).

What can we learn from this? For starters it reinforces our earlier contention that light works as a unifying factor within Creation. By extension, we can assert that the ratio of light to dark actually results in this unity. Proportioning light in a 3 to 5 relationship is key. For the interior light designer, factoring in the shadows proves just as important as calculating the illuminated areas.

Furthermore, in Kabbalah the Fibonacci numbers are called ‘love numbers’ (misparai ahavah) in part due to the word ahavah (love) equalling 13 in gematria as well as the ‘coupling’ or ‘mating’ of numbers in the series to birth subsequent generations. This being said, ‘oneness’ (echad) and ‘love’ (ahavah) demonstrate an equivalency (‘one love’: Bob Marley…anyone?).

In Kabbalah we also find another example of light relating to unity in that there are exactly thirteen (echad ‘one’) synonyms for light in Hebrew:

(אור,בהר,זהר,נהרה,נגה,צהר, זיו,חשמל,יקר,בהק,זרח,הלל,טהר)

For all of the multitude of words for illumination, they nonetheless add up to a unifying factor–many lights as one (as creating oneness) on the day of the one (which is day one). Moreover, the Book of Formation (Sefer Yetzirah), puts forth alternative situations that this unity applies to in that every aspect of Torah and Creation possess the concomitant dimensions of ‘World,’ Year,’ and Soul.’ Representing the spacial (world), temporal (year) and conscious of the observer (soul) respectfully, these three dimensions all appear along with the word echad (oneness) in the opening of the Genesis narrative.

On the third day (Genesis 1:9) of the week of Creation, all of the water under the heavens are gathered together in ‘one place’ (makom echad) as a reference to spatial unity. Taken in tandem with our ‘one day’ (yom echad) which represents temporal unity, we have defined the oneness of space-time. What about our third dimension of ‘soul’ or the consciousness itself (consciousness that peers into space-time)? For that, flip forward to Genesis 2:24:

“Therefore, a man shall leave his father and his mother and cling to his wife, and they shall become one flesh” [emphasis mine].

‘One flesh’ (l’vasar echad) reflects the unity of the human condition or the marriage of masculine-feminine dynamics within consciousness. Amazingly, all three verses corresponding to the world, year, soul, have exactly thirteen (echad or ‘one’) words each. Thus, human consciousness is also ‘one’ and shares in the same unity possessed by space-time.

From these tripartite unities, we can extract a profound lesson for our interior lighting. Not only does lighting have to ultimately account for and embrace light and darkness, it has to accommodate space, time and the perspective or consciousness of space and time. Beginning with space, any room that we wish to illuminate must be done with an eye towards unifying that space. The windows, doors, walls, furniture are gathered and held together by the light that shines on them.

Since there is an unfortunate tendency to think of the elements of a room as timeless and static, we sometimes only plan to light them in a generic, timeless or universal way. Yet, anyone who has insisted on checking out a new perspective home with a real estate agent at different times of day realizes how critical time is. Natural light makes everything look different. Morning light comes in from a different direction than evening light and it potentially makes having a cup of coffee at the breakfast table a blinding experience without the right window shades installed. That ultra-bright halogen bulb may present no glare problems at high noon, but at night when watching videos, its glare destroys my viewing experience. The pantry cabinets are easy to rummage through looking for an afternoon snack, but try this same food run when you get a case of the midnight munchies and that 20 watt bulb hanging from the ceiling won’t do the trick. All I get is an annoying shadow of myself cast over my prized bag of potato chips.

Thus, taking time into consideration is crucial for our lighting design. We need to think of the room as a dynamic interplay of natural and artificial lights as the hands of the clock cycle round and round. Adjustable lights (dimmers) and shades, tinted glass and reflective surfaces team up to effectively navigate the temporal flux of the lighting and its impact on the house. Instead of weaving together space, they connect diachronic perspectives of the room. Thus, ‘time binding’ proves to be one of the essential unifications incorporated in the lighting design.

Lastly, we have the unity of perspective. Consciousness is really a double figure comprised of male (observer) and female (observed) which have to unite and cleave together (note that in Kabbalah both biological male and female play both parts of observer and observed). The joining of perspectives, the marriage of observer and observed, means that the lighting arrangement of the room should ideally look good from any vantage point (observer) and all that is looked upon (observed)–no matter where it is positioned–should likewise find favor.

Thinking of the soul or human dimension within the space-time of the room qualifies as the ergonomics of lighting design. Furthermore, the humanizing or soulful element of the lighting permits the manipulation of the space of the room at different times. Objects in the room, as well as the room itself, becomes ‘things’ ready at hand for human repurposing (this is partially Heidegger’s observation following his distinction between object [abstract] and thing [appropriated by or related to the human realm and human usage]). If we are to be effective designers, then the prioritization of this threefold unity must take top priority and peak with the personalization of space-time.

All eight levels of light and darkness will be explicated one by one in Part Thirteen.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/inspiring-interior-design-part-13/

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)