Determinism and Freewill are Brothers (Part 1)

By Asher Crispe: April 29, 2011: Category Decoding the Tradition, Inspirations

Who is driving the bus?

There is no joy in discovering that a bunch of kids are speeding off to nowhere completely unsupervised. Yet, this is precisely how we tend to feel when faced with the prospect that this world and its crazy history might not have a direction after all, much less an authority figure who can explain why we’re going this way and clue us into where we are going.

There is no joy in discovering that a bunch of kids are speeding off to nowhere completely unsupervised. Yet, this is precisely how we tend to feel when faced with the prospect that this world and its crazy history might not have a direction after all, much less an authority figure who can explain why we’re going this way and clue us into where we are going.

Panic sets in: we didn’t sign up for this—to leave nowhere to be in the middle of nowhere to ultimately, after a long exhausting haul, get to the heart of nowhere? There must be a map somewhere! Perhaps the bus is high tech and remote controlled? An experiment in independence set up to give the impression of driverlessness? Or are we meant to fight as only kids can for a turn at the wheel? Can we entertain the notion of a ride where we all steer together? What exactly is the plan?

There is a plan? Isn’t there?

As a child I used to enjoy reading a series of books called “Choose Your Own Adventure.” Basically, at the end of each chapter, which was a relatively self-contained scene and plot point, the reader would be given instructions and clues about the available options awaiting exploration if one would skip around the book. Due to its non-linear structure, more than one story would unfold depending on the choices made in the order in which one read.

(Some are convinced that this created legions of undisciplined readers who would grow up to steal forward glances in their books and thereby spoil the surprise of reading or even more brazenly read the ending first before deciding whether or not to commit the time to reading the entire book.)

While even a pre-philosophic youth can sense that the authors set up a limited variety of choices that would lead the reader down only so many roads, nonetheless, the feeling of freedom to proceed according to personal selection seemed real (at least as a child).

We are very attached to our choices. Freedom to choose tends to be speak to the core of the idea of freedom. Yet, choices happening in real time, brought to us live and unedited, would likely have the effect of compromising any grand scheme. Doesn’t it stand to reason that there was only one true choice on day one, at go, when we laid in a course whose trajectory would come to be tragically unalterable?

Do plans—be they mine or some Divine Other’s—eat into our freedom? Is a plan a plan only when its full design is realized? Can we still be free to choose if those choices are supervised? Are prerecorded choices impostures masquerading as the real thing?

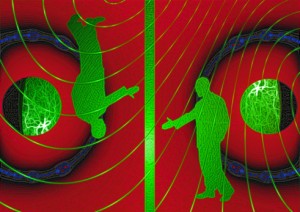

All of these questions are but sparks floating out of an ancient metaphysical fire. The quandary of freewill verses determinism has always been incendiary with each side attempting to consume the other. Hoping to exploit some weakness in the argument for peaceful coexistence, a winner must emerge. Like matter and anti-mater, they must repel each other. Most framing of these questions uses the logic of exclusion: either/or: take it or leave it: all or nothing. So much for the spirit of compromise.

Tracing the Jewish intellectual heritage of these questions transports us back into the opening drama of Genesis. Our chief protagonists are Adam or Adom, who in Hebrew refers to the universal human condition in Jewish mystical readings, while Eve or Chava relates to chavayah or experience. Thus our edenic marriage of Adam and Eve is figuratively the coupling of ‘human experience’. They in turn produce Cain and Abel and a bit later on Seth, thereby completing this ‘first family’.

Sibling rivalry is anything but new. The Genesis narrative paints the conflict of two brothers Cain (Kayin in Hebrew) and Abel (Hevel) in grim terms that resonate from within the primal tales of our origins and cask a long shadow over the entirety of human history. As the story goes, Kayin rose up and murdered his brother Hevel out of jealousy. As a first murder, we find that the Torah lays down the facts of the case including the motive in a straight up fashion.

Each of the brothers brought an offering to God. Kayin offered inferior produce while Hevel contributed from the firstborn from his flock. Not surprisingly it was Hevel’s offering that found favor due to its being the best of what he had. This in turn vexes Kayin who, overcome with rage, rises up and slays Hevel.

According to the Arizal (16th century kabbalist Rabbi Yitzchak Luria) Kayin and Hevel are prototypical souls that are reincarnated over and over so that they can have rematch after rematch revolving around this essential conflict between them. Furthermore, the Arizal continues and suggests that each person possesses a spiritual charge that is inclined to be more Kayin-like or Hevel-like. In terms of our psycho-drama, this means that we are encumbered with the spiritual issues of either brother and readily get caught up in the conflict when both ‘brother principles’ are proximate to one an other.

For the Arizal, the recurring representational force of the brothers stems chiefly from the ‘theoretical’ reactions to the jealousy and murder. This is no pulp fiction. The issues are real and ongoing.

For the Arizal, the recurring representational force of the brothers stems chiefly from the ‘theoretical’ reactions to the jealousy and murder. This is no pulp fiction. The issues are real and ongoing.

According to kabbalists, the inner dimension personified in Kayin is the deep conviction that everything is Divinely ordained, that every detail of reality right down to the simplest of our actions falls under the rubric of hashgachah pratit or Divine Providence. Like a top notch criminal attorney, Kayin dismisses his personal responsibility for his acts, arguing to God that this was all predetermined. Divine Providence in the Hebraic tradition plays a similar, but by no means identical role, to that of determinism in the Greek philosophic tradition. Kayin maintains that since God is really the one in charge of the world and not only sees what will happen before it happens but also has everything happen according to His Divine plan, then we, as mere lowly creations, have no real choice in the matter.

If all of our acts are Divinely directed, then how can there be room for personal responsibility? In other words, Kayin has no problem with Divine Providence. He believes in a driver of history and a grand plan. Yet, this is precisely where his jealousy arose from. His jealousy of his brother Hevel was really a jealously of the abstract notion he embodied—the idea of free choice.

In Kabbalah, Hevel’s address to God reads directly against the grain of Kayin’s. For Hevel, he has no problem with freewill. He acts freely in selecting his offering for God and he believes that Kayin acted freely in murdering him. Consequently, Kayin is guilty and must bear the burden of that guilt. Justice demands personal responsibility.

Hevel’s issue is with Divine Providence. As the victim, he can only wonder as to how God could have allowed this to happen. How was this part of the plan? Is there a plan? The Supervisor needs to get involved. Did God intend for this to happen or not?

In short, each brother wrestles with the natural mode of spiritual being of the other. Kayin handles Providence well but gets hung up on freewill. Hevel, in turn embraces freewill but can find neither rhythm nor reason for Providence because otherwise, how could have his death been part of the plan?

Termed bichirah chofshit, free choice is personified not by the first born brother (Kayin) but by the second brother Hevel reflecting its status as a second order principle. Freedom stands in contrast to an earlier ‘first born’ perception of determinism—like Hevel against the background of his older brother Kayin. The choice only becomes meaningful when it seems to alter the plan. Like the exception to a rule, the keepers of the plan can display jealousy at those who have the freedom to choose whether or not to go along with that plan. This was Kayin’s underlying jealousy of Hevel. Determinism becomes jealous of freewill and threatened by it, while attempting to extinguish it. Determinism cuts short the life possibilities of freewill.

To recap, determinism or Divine Providence and freewill are like brothers. They are co-extensive concepts. Moreover, in Kabbalah, these sibling ideas become questions which constitute the first offspring of human experience (Adam and Eve). They are part of the deep ancestry of ideas from the cradle of human civilization and they are reborn with each new conflict in the unfolding of history. They are a necessary ‘base-pair’ of our intellectual DNA and a core component of life.

To recap, determinism or Divine Providence and freewill are like brothers. They are co-extensive concepts. Moreover, in Kabbalah, these sibling ideas become questions which constitute the first offspring of human experience (Adam and Eve). They are part of the deep ancestry of ideas from the cradle of human civilization and they are reborn with each new conflict in the unfolding of history. They are a necessary ‘base-pair’ of our intellectual DNA and a core component of life.

Determinism and Freewill are Brothers (Part 1),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

very enjoyable and interesting.

Wow. This explains a lot of history and the squelching of Judaism.

So, now that we know that they are brothers, we can pre-empt the jealousy, if we choose!

I’m always amazed by how much I have to learn about things I think I know pretty well. Thanks for amazing me.

I take my previous comment back. How would Kayin know that Hevel was operating by a different principle than himself? He didn’t think that Providence ruled only him, did he? Therefore, he would be angry because there was no justice in the reward to Hevel.

But this is what really happened: Kayin, the first born was doted on. He never had to work for his parents approval, so he didn’t value it. Hevel, on the other hand, had to work to gain their approval and therefore valued it. So, they both acted accordingly with respect to the larger figure of authority, but this time, Kayin didn’t get the automatic approval he expected. He displaced his anger at G-d onto someone weaker, his brother.

Shouldnt it be the reversed? Maybe i read it wrong but you mention Kayin being the embodiment of free choice. But shouldnt he be the embodiment of free choice while Hevel is the embodiment of determinism. Hevel represents being ‘determined’ by Above, eliciting Divine favor while Kayin represents the man who made the wrong choice. Thus Hevel (determinism) is sort of undone by Kayin (free choice; he had the full fledged free choice) to kill Hevel. That is why it is sort of ironic that Hevel’s end is with another’s free will and Kayin also is ‘chosen,’ to roam the earth. Only to be shot with a bow and arrow accidently by one of his descendants, Lemech. (I think this is from a midrash). Thus Kayin’s free will is undone by Hevel’s determinism (ie it wasnt Lemech’s choice to kill Kayin). Thus both concepts struggle with one another in an inter-inclusive way. BSD