Songs of Myself (Part 3)

By Asher Crispe: June 25, 2014: Category Inspirations, Simple Rhythms

“Song is existence”

– Rainer Maria Rilke Sonnets to Orpheus (1,3)

Our fascination with music may well be more than something that we enjoy coincidentally as an experience that approaches us from the outside in. Beyond the external trappings, music is constitutive of who we are. It defines home and seeds the self as it addresses all of our diverse modes of being. Yet the medley of our lives varies in its emphasis over time as it affects different parts of the soul. There are songs for all occasions. Certain types of song speak to me and allow me to speak through them when they befit the moment.

Our fascination with music may well be more than something that we enjoy coincidentally as an experience that approaches us from the outside in. Beyond the external trappings, music is constitutive of who we are. It defines home and seeds the self as it addresses all of our diverse modes of being. Yet the medley of our lives varies in its emphasis over time as it affects different parts of the soul. There are songs for all occasions. Certain types of song speak to me and allow me to speak through them when they befit the moment.

Examining the book of Psalms (which is most closely associated with King David, the great soul singer of Israel), the sages note in the Midrash that there are ten synonyms for song or music in Hebrew. Given its status as the primary ‘libretto’ for the spiritual services that were sung in the Temple, we might expect that the standard repertoire would contain not only something for everyone, but also something for every aspect of the self.

As with all of the classic sets of ten that appear in the Torah (ten plagues, ten commandants, etc.), these ten parallel the ten powers of the soul. Our being is structured in terms of these powers which themselves correspond to the channels of Divine revelation or self-expression, as well as the dimensions of creation known in Kabbalah as the sefirot. They progress from the abstract intangible realm of the unconscious through the faculties of mind and emotion until they egress into the world in the form of action and concrete influence on others.

Modeling these relationships between musical experience and the powers of the soul reinforces the idea that there are not real synonyms in Hebrew. From our work with other languages, when tasked with a writing assignment, we might be convinced that word choice is merely a stylistic matter. An author’s selection reflects the contingency of vagrant meaning. Preference is given to shaking things up a bit and adding some variety for mostly ornamental and aesthetic purposes, but deep down there is no rhyme or reason for having inked one word over another when they all seem to accomplish the same thing.

Not so in Hebrew. Part of the notion of it being a “Holy tongue” stresses the singularity of every word. There is no redundancy. As the building blocks of Creation–the signifiers which engender the signified–Hebrew language mysticism values the precision of word choice and word placement. Commentators confirm this as they pour over texts trying to ascertain why this or that word is employed here now. On some level, there is an unabated sense that it could not have been otherwise. Not that our words suffice as stand alone modules, but rather they act as zones of intensity within a larger meshwork or complex system. They are delicate deposits of roots and branches which deserve the greatest of care. The payoff in this value proposition comes when we realize how they map onto groups of phenomena and facilitate a grander circulation of ideas than we might have thought possible.

In view of this, the attraction of the ten synonyms for song and music is not in their general equivalency but in detailing the nuances of each of these terms such that they may illuminate the dark and silent furrows of our inner world. We graduate from a ‘song of myself’ to ‘songs of myself’ when we meditate on how every aspect of our person has its own special song. Consequently, the task set before us is to lay down the connecting lines that fill in this picture with all of the riches that it has to offer.

Let us begin at the top. The power of the soul that fashions the proto-self is called the keter or ‘crown’ in Kabbalah. As a symbol of the superconscious or unconscious, the crown sits above the conscious mind and surrounds it. If we imagine the skull as a type of crown, then we can also see that it rests in a place which is physically higher than the sensory apertures mounted on the face of a person. Abstractly, this denotes the extra-sensory, super-rational quality of the unconscious. Consciousness, and the proper domain of rationality, reside within its envelope. While my securing of a self-reflective identity–my separateness as an ego–only really emerges from within the conscious mind, the primacy of human experience takes us back to early childhood development where there was either no “I” or barely and “I” to speak of.

To give an everyday illustration of the crown, we may refer to the common social situation whereby a friend tells me a joke and I don’t get it. The references are lost on me. I can’t place it. It fails to penetrate into my mind in the sense that I can’t contextualize its meaning within the framework of what I already know. In response, I gesture that I don’t understand by passing my hand over my head indicating that I didn’t get it. “That went over me,” I say. But I heard it. I heard it without really hearing it. I am left puzzled. What this common behavior displays is our innate sense of what a crown is. My head is simply the location of my conscious mind, and that which is over my head represents my unconscious crown. The ungraspable, that which transcends the intellect, is ultimately experienced as mystery and wonderment (hafalah).

The musical term which relates to the crown is called ashrei. Taken from Psalms like the rest, it enjoys a special liturgical significance as a key recitative part of daily prayer. On the face of it, the word means “happy,” but it more specifically hints as the unconscious source of our contentment in the serene pleasure (ta’anug) in the soul. What really makes us happen is not always rational nor it is the product of our conscious mind. It stirs within the depths of the soul. When we are wondering at ourselves, when we are mystified by our own motivations, we are peering into the unconscious crown. Every time we cannot trace the production of our drive to some mental process that we can lay bare in purely demonstrable terms that can be apprehended by our understanding, we are picking up on the influence of the crown.

Ashrei melodies also have the additional connotation of the kindred word hashra’ah which means something like an ‘indwelling infinite inspiration.’ When combined, the various meanings carry a sense of an uplifting inspired musical experience. Since we speak of having our ‘minds blown’ or being ‘out of our minds’ when we are overpowered by the immensity of some experience, it follows that the unconscious is the uncharted territory that we are carried away to. Music that produces wonderment, that entices us with the great mysteries, that leads us past our mental warden and into an expansive state, is key worded with the term ashrei.

By turning the ‘something’ that I think I am back into an unthought ‘no-thing,’ the listener is transported into the beyond. In traditional Chassidic melody, there is an entire category of songs that create devekut or “ecstatic cleaving” with the ‘Big Other.’ This kind of music breaks down the borders of self and non-self and enters a person into an experience of psycho-synthesis. So the question that we each ask ourselves is, “what kind of music helps us to transcend?” Is it a trace induced by levity? Or sublimation of the ordinary into the extraordinary? For those unfamiliar with this form of Chassidic song, perhaps there is some other musical reference that can be applied. Is it the transmutation of self fixated on the rhythmic beating of the rave, the letting go of control in the midst of a jazz improvisation session where one must feel the way forward with renounced expectations, or the sublime hope of humanity piercing the heart with the choral finale of Beethoven’s universally recognizable 9th symphony proclaiming, “Ode to Joy?” Many report of having had different musical performances permeate their entire being. Souls are soaring to some ineffable quality.

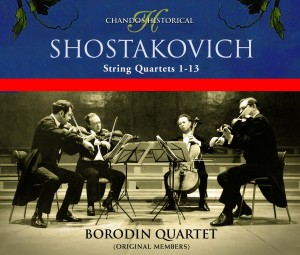

The desire that fuses pleasure and will that is found in edifying music approaches the prophetic (the prophets of ancient Israel even used music to induce states of prophecy). Perhaps each of us has a different trigger. Personally speaking, I am ‘happy’ with all of it. I love the open texture of music and I enjoy all of the places it takes me. At the same time, I believe that you have to slow yourself down and be present to the faintest quivering of the bow–the arresting of time that electrifies the slow movements. From my own listening history, I still recall the transcendent mood of the original Borodin Quartet recordings of Shostakovich’s Sting Quartets. They have passages which progress at an almost glacial pace but they provoke the spirit and facilitate our slipping into personal reveries and all-absorbing contemplation amidst a musical odyssey.

The desire that fuses pleasure and will that is found in edifying music approaches the prophetic (the prophets of ancient Israel even used music to induce states of prophecy). Perhaps each of us has a different trigger. Personally speaking, I am ‘happy’ with all of it. I love the open texture of music and I enjoy all of the places it takes me. At the same time, I believe that you have to slow yourself down and be present to the faintest quivering of the bow–the arresting of time that electrifies the slow movements. From my own listening history, I still recall the transcendent mood of the original Borodin Quartet recordings of Shostakovich’s Sting Quartets. They have passages which progress at an almost glacial pace but they provoke the spirit and facilitate our slipping into personal reveries and all-absorbing contemplation amidst a musical odyssey.

Next we proceed to musical forms which speak to the intellect in Part Four.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/songs-of-myself-part-4/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/songs-of-myself-part-2/

Songs of Myself (Part 3),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)