The “Organization” of Law (Part 6)

By Asher Crispe: May 12, 2014: Category Inspirations, Quilt of Translations

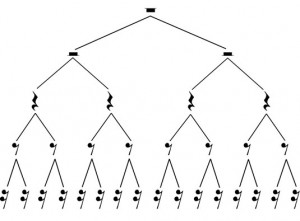

While organs fill, sinews connect. Our legal ‘corpus’ (in the dual sense of being both a collection of texts and a body) has carefully placed limbs, organs and bones which have to work together as an ensemble. Representative of the positive commandments, their anthropomorphic arrangement suggests an underlying legal system designed for coordinate action. If we consider them as locations which could be abstractly mapped as plot points, then what connects between the dots? The answer is the negative commandments. They could be likened to the interstates which link between the states, the discursive pathways that travelers must navigate on the way from township to township.

Rather than the common expression ‘for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction’ in the Newtonian sense, we might venture to say that ‘for every positive action there exists a necessary interval of inaction’ which surrounds it, spanning the gap to the next licensed action. Our permissible activities are swimming around in a fluid of that which does not materialize. The King’s highway is continuously flanked by the ‘road not taken.’ The space of the negative works in concert with the positive. For this reason, the kabbalists equate the 365 negative commandments with an idealized set of 365 sinews in the body.

Rather than the common expression ‘for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction’ in the Newtonian sense, we might venture to say that ‘for every positive action there exists a necessary interval of inaction’ which surrounds it, spanning the gap to the next licensed action. Our permissible activities are swimming around in a fluid of that which does not materialize. The King’s highway is continuously flanked by the ‘road not taken.’ The space of the negative works in concert with the positive. For this reason, the kabbalists equate the 365 negative commandments with an idealized set of 365 sinews in the body.

Why sinews? What about fibrous tissue—that connects muscle to bone or bone to bone—is relevant here? For starters, they supply the spacing that is at once a separation and a bridge. Recognizable to the musicians amongst us as the rests which break up a succession of notes (these negative spaces connoting the absence of sound) also assist in providing the much needed structure to a music phrase. They facilitate communication. In a certain sense, the same goes for the sinews of the body.

A sinew or ‘gid’ in Hebrew has a rich constellation of associate meanings: gid stems from the root Gimel-Vav-Dalet which means to ‘connect’ while its close cousin Gimel-Dalet-Hei carries the opposite sense of ‘separation’ and ‘division.’ Most importantly, the root Nun-Gimel-Dalet (an exceptional drop letter root where the ‘Nun’ falls out much of the time) gives us the word haggadah (the ‘tale’ which is read at a Passover Seder) which is a synonym for communication or storytelling. This last root is the most interesting because Nun-Gimel-Dalet, besides declaring something, also forms the word neged which has to do with opposition. Thus, the interplay between the positive and the negative instantiates (both as an example or occurrence of something and as the institution of legal ‘suit’ in the rare legal usage) communication.

While all of the 248 positive commandments are indicative of a rechem or womb (248=rechem), the number 365 is expressed with the word shesah (Shin-Samech-Hei) which may be re-vocalized as shisah–suggesting that the negative commandments are all a form of avoiding ‘incitement’–or alternatively as shasah–a kind of ‘plundering,’ a stealing by force, a dishonest acquisition. All toll, the prohibitive amounts to a violent provocation whereby a person transgresses the boundary of what belongs to the self and what is non-self. The ‘don’t do’ signals the encounter with the ‘not-me’–the force of self-alienation or displacement. As sinews, they suggest lines of tension which contract and relax within the legal system.

Just as the positive commandments were embodied externally as limbs and organs and internally as bones, the negative commandments follow the same pattern with the outer correspondence to the sinews and tendons being joined by the inner parallels with the blood vessels. Here the color scheme matters. Bones are white which is the associate color for loving-kindness (chessed) in Kabbalah, while blood (or blood vessels) are identified with red which compares with severity (gevurah). Of course loving-kindness and severity already capture the dialectical flavor of the positive and negative commandants. However, it remains enigmatic as to why the circulatory system is evoked here.

On some general level, the circulatory system is obviously about circulation–the continual movement which can be thought of as constant displacement. Blood which settles in its place too long is toxic and, in the case of a clot, is potentially fatal. Not so for our bones and organs. They need to maintain their relative placement and not move within the context of the larger body (no one wants to find their heart at the bottom of their foot!). Being an infrastructural dimension which surrounds all of the body (they relate to the light which ‘surrounds all worlds’ [ohr ha’sovev kol olmin]) they symbolize that which is ‘neither here nor there,’ or the ‘non-space’ within space.

However, to shed some additional light on this mystery, we have to juggle one further correspondence: the 365 days of the solar year. This is particularly unusual in that Hebraic time normally works according to the Hebrew year which is itself build upon the lunar calendar. The day really includes both the day and the night as the Torah states in Genesis 1:5 “…and there was evening and there was morning, one day.” Activities fill the daytime within the day, whilst the night within is comparatively reserved for rest. Likewise, we find that arteries pulsate (which is akin to the exertions of the day), while veins do not (a sign of the rest of the night).

For the negative commandments, each one is doubled in that we have both an active and passive resistance to not doing something. When the situation arises whereby we feel compelled to do something impermissible (one need look no further than unhealthy food cravings) and we manage to summon the inner strength to subdue our appetite, then we can be said to have taken an active stance against such a behavior. We consciously choose not to go through with it. Therein lies the ‘pulse’ within the daylight part of the day which is analogous to our conscious mind. In comparison, when we feel no arousal towards something prohibited–whether out of a lack interest or from simple ignorance of the existence of such an option–no real choice was made. This passive abstinence has no pulse. It remains drowned in the unconscious of the soul–the night of the self.

Finally, who in the narratives of the Torah gains prominence as a righteous individual not only from what he does positively, but also (and perhaps more significantly) from what he refrains from doing? Yosef (Joseph). He is even known as Yosef ha’tzaddik (Joseph the righteous) in part because he did not give into the the sexual enticements of Potiphar’s wife (note that Potiphar was the captain of Pharaoh’s guard who appointed Yosef as the overseer of his entire house [see Genesis 39:10]). Interestingly, the expression ‘Yosef ha’tzaddik’ equals 365 which the mystical tradition highlights as a further support for his quality of character, deriving from his ability to remove himself from a problematic situation and act to not act within the context of the prohibited.

Finally, who in the narratives of the Torah gains prominence as a righteous individual not only from what he does positively, but also (and perhaps more significantly) from what he refrains from doing? Yosef (Joseph). He is even known as Yosef ha’tzaddik (Joseph the righteous) in part because he did not give into the the sexual enticements of Potiphar’s wife (note that Potiphar was the captain of Pharaoh’s guard who appointed Yosef as the overseer of his entire house [see Genesis 39:10]). Interestingly, the expression ‘Yosef ha’tzaddik’ equals 365 which the mystical tradition highlights as a further support for his quality of character, deriving from his ability to remove himself from a problematic situation and act to not act within the context of the prohibited.

In conclusion: the somatic conditioning of law reinscribes all Jewish notions of legality within the horizons of our immediate human experience. We are the living embodiment of the law. It structures us just as we structure it. Hence, any contemplation of Torah-based jurisprudence must pass the prism of this most human of referential frames. By doing so we encounter within ourselves and within the law the foundational features of the body as manifestations of both the positive and negative forces with which we govern our actions and define ourselves.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-organization-of-law-part-5/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/the-organization-of-law-part-1/

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)