Food for Thought and Thought for Food (Part 4)

By Sara Esther Crispe: April 7, 2014: Category Decoding the Tradition, Inspirations

The Psychology of Chewing Cud and Split Hooves

We all know that young children need their food cut up for them. We can’t rely on them to break it down themselves or even necessarily chew it through. So to protect them from any problems we ensure that the piece they put in their mouth is small enough that if it goes down whole it will be OK.

We all know that young children need their food cut up for them. We can’t rely on them to break it down themselves or even necessarily chew it through. So to protect them from any problems we ensure that the piece they put in their mouth is small enough that if it goes down whole it will be OK.

The more any of us chew through our food, the easier digestion becomes. More so, any dietician will tell you that if you want to lose weight, chew longer. The more the food is in your mouth, the longer you can savor its taste and texture and the more satiated you will feel once you swallow it.

When it comes to keeping kosher, there are two distinguishing features required of all land animals: they must have split hooves and they must chew their cud.

While chewing the cud is not the most pleasant concept physically, from a spiritual, intellectual and emotional perspective it is quite vital and relatable. Chewing the cud takes the necessity and importance of breaking down what one is going to consume to an entirely different level. Humans chew our food. As we just discussed, the more the better. And while we chew the food remains on the level of our head rather than the level of our stomachs.

With a human it is clear that our head is above our stomachs (body) with the idea that the mind should rule over and direct how one behaves. Even with land animals who are on all fours, the head is still elevated above the rest of the body with the same idea that there should be thought guiding our action. So the longer we think though, work through, break down and really chew what is in our heads, our minds, before we allow them to become a part of ourselves, the healthier we will be.

But chewing the cud reminds us of another level we must partake in. Physically this means an animal chews and swallows its food, then regurgitates it, chews it again and then swallows it for a second time. And so must we. Fortunately not physically but on every other level. It is vital that periodically we examine who we are, what we believe, what we have already digested from the world around us, and bring it from our behavior and actions back into our minds. Once we remove it from our bodies, we have the ability to rethink these attitudes and ideas and determine if they are still right for us. If so, we digest again. If not, we ensure that we rid ourselves of what is no longer healthy.

The word in Hebrew for a tooth is ‘shen’ which is the same root as the words: “to teach” and “to change” and likewise is the word for “year” representing time. Over time we shift our ideas about ourselves and others. We continue to learn more and then take that knowledge to impact the world around us. And it is the teeth that are what break down what we consume, make it manageable, understandable, ready for digestion. An adult mouth has 32 teeth which according to Jewish Mysticism represent the 32 pathways of wisdom. (Interestingly, we mainly chew with our back teeth, those which we refer to as our ‘wisdom teeth’!)

The second feature required of any kosher animal is that it must have split hooves. Not all land animals even have hoofs at all, but of those that do, it is essential that it has a complete split.

The hoof can be likened to a shoe on the animal, it is the barrier between the skin on the bottom of the foot and the ground. It ensures that there not be complete contact with the earth but that there maintain a constant distinction.

We most definitely need to live in the world. We need to connect with and be aware of what is happening around us. And the world represents our we physically sustain ourselves in life. We eat, we sleep, we work, we engage. And yet, even in the seemingly mundane, we must never lose sight that everything can and must be elevated. Everything we encounter has holiness embedded and often hidden within.

Simultaneously, we need to learn the importance of distinctions in life. Not everything is the same. Not everything is equal. And while we strive for inclusivity, we must also recognize that there are essential differences and right can never be mixed with wrong. Even two “rights” can be wrong if combined (as was discussed in Part 2).

And then there are the fakes in our lives.

We all have had to deal with impostors. Those that purport to be one way when in truth they are nothing of the sort. And being fooled hurts. If we believed someone cared for us who was just using us or invested money in someone we felt was trustworthy only to discover we were robbed, it leaves us feeling vulnerable and unsure of ourselves. It makes us really need to rethink before we make decisions in the future.

The Torah very clearly warns us of these impostors when it comes to animals who pretend to be kosher. And we are advised to never judge superficially or externally but to always put in the time and effort to really research and determine if both of these required qualities are there. Once again, before we swallow, we must ensure we have thoroughly chewed and used those teeth, those channels of wisdom, to break down what we want to integrate into our lives.

There are a few animals that are even given as examples. In all the cases they have one of the two necessary elements for a kosher animal. And while one could mistakenly think that one quality is better than none, it is actually more dangerous. When neither quality is present there is no question that it is not right, but the closer it gets to being right, the more we are willing to believe it. That is why the most powerful lies are the ones that are almost completely true.

We even see this in the structure of the words themselves for “true” and “false.” The Hebrew word for falsehood, for a lie, is sheker which has the three letters, shin, kuf and reish. All three of these letters come to a single point or “leg” at the bottom. They are not on solid ground but could easily be tipped over. The letters, however, for the word “truth” which is emet is comprised of an aleph, mem and taf. All three of these letters are structured on two solid “legs” on the ground. They cannot be easily pushed over as there is a foundation.

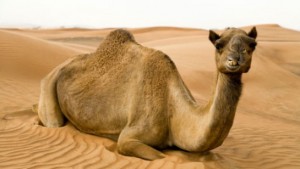

So the Torah tells us to look carefully. It describes how a camel chews its cud, yet doesn’t have split hooves. And yet, when the camel sits, it hides its hooves so that the non-kosher element is not easily detectable. The pig on the other hand shows off its hooves as they are clearly split. And yet it doesn’t chew its cud. The pig also has the inability to turns its head (its intellect) upward and see the sky. Even though its head is higher than its feet, its gaze is always downwards with no recognition that there is something bigger or greater than itself in this world.

So the Torah tells us to look carefully. It describes how a camel chews its cud, yet doesn’t have split hooves. And yet, when the camel sits, it hides its hooves so that the non-kosher element is not easily detectable. The pig on the other hand shows off its hooves as they are clearly split. And yet it doesn’t chew its cud. The pig also has the inability to turns its head (its intellect) upward and see the sky. Even though its head is higher than its feet, its gaze is always downwards with no recognition that there is something bigger or greater than itself in this world.

To summarize: Every time we eat, we have the opportunity to choose what it is we are going to consume. Keeping kosher has engrained within it that just as we must work through and process what we will digest in our lives, so too we only eat animals that have worked through not once, but twice, all that they consume. More so, we only eat animals that have a barrier between themselves and the ground and a separation reminding us that there is a clear right and a clear wrong in the world. And regardless for how close to the truth something may seem, we must always be careful to seek and ensure the veracity of all its aspects and ‘marks’ of distinction.

In Part Five we will discuss the kosher signs for sea animals: Fish and Scales

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/thought-for-food-and-food-for-thought-part-5/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/food-for-thought-and-thought-for-food-part-3/

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)